When the Turks established their rule over Anatolian lands, they demonstrated examples of civilization that would still be considered significant today in many fields. The matter of standardization is among these achievements. Nearly five centuries ago, standardized regulations were established and strictly enforced according to the local characteristics and production varieties of cities such as Bursa, Edirne, Sivas, Erzurum, Diyarbakır, Çankırı, Aydın, and many others. At the founding of the Ottoman Empire, the Seljuk-era Ahi guild system was present. Within this system, tradesmen self-regulated through autonomous oversight, with no direct state intervention. Over time, however, the Ahi system transitioned into a state-controlled framework.

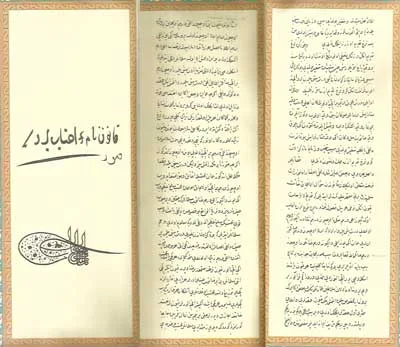

In 1502, under Sultan Bayezid II, this transformation was formalized through new laws that brought the Ahi system under state supervision. The “Kanunname-i İhtisab-ı Bursa” (Bursa Municipal Law), whose original copy is held at the Topkapı Palace Museum, is considered Turkey’s first municipal law and a significant regulatory document in world history.

A writing displayed on the wall of the Turkish Standards Institute (TSE) building in Ankara notes that Sultan Bayezid II implemented the world’s first standards.

Kanunname-i İhtisab-ı Bursa: A Milestone in Legal History

In 1502, Sultan Bayezid II issued the “Kanunname-i İhtisab-ı Bursa,” which standardized the sales regulations for goods such as bread, pastries, meat, fruits, and vegetables. Alongside similar codes in Istanbul and Edirne, this law is among the most significant from his reign.

It is not only the most comprehensive municipal law of its time but also recognized as the first consumer protection law, first food regulation, first standardization law, and first environmental regulation in the world.

Prepared by Mevlânâ Yaraluca Muhyiddin -a legal expert well-versed in Ottoman traditions and Islamic law- the law was drafted between 1502 and 1507.

The inscription on the wall of the Turkish Standards Institute (TSE) building in Ankara shows that Sultan Bayezid II implemented the world’s first standards.

Addressing Corruption and Ensuring Quality

From the introduction of the law, it is understood that previous regulations had become ineffective. Issues like hoarding, bribery, favoritism, and negligence were widespread. Problems such as counterfeit and low-quality goods, improper weight measurements, and expired or damaged products had increased, leading to disputes between buyers and sellers.

The Kanunname introduced strict, standardized regulations tailored to Bursa’s local conditions and product diversity.

For example, in the case of bread, the law addressed not just price and weight, but also how much flour should be obtained from a given quantity of wheat, the permitted stock levels in bakeries, and penalties for underweight or underbaked bread.

Comprehensive Standards and Continuous Inspection

Thanks to this law, almost all agricultural, animal, and industrial products were regulated with standards concerning both quality and price. A special organization was established to monitor these standards consistently.

In determining these regulations and fixed prices (narh), opinions from producers, experts, citizens, and relevant stakeholders were gathered and documented.

Separate sections were allocated for clothing and durable consumer goods. For instance, the durability period of footwear, or the width and length measurements of fabrics and mats, were specified, representing a complete move toward standardization.

In the Ottoman period, apprentices were both educated and supervised by their masters, who ensured product quality; laying the foundations for today’s concept of quality assurance.

Such a detailed and sophisticated chain of standards made this document unique even for its time.

Sample Texts in the Regulation

Butchers: When the butchers, expert assessors, and some of the city’s notable figures were gathered and asked about the regulations applied to meat, most of the devout and trustworthy Muslims present said that, in the past, the fixed price (narh) for mutton was determined three times a year, in three different categories. Initially, it would be sold at 250 dirhams, then at 300 dirhams, and during winter at 200 dirhams. However, for the past four or five years, mutton has no longer been sold at 300 dirhams at all. Instead, it has been consistently sold at 250 and 200 dirhams. When asked why the 300 dirham price was no longer applied, the butchers provided several reasons. First, in the past, a dock tax of one akçe per sheep was charged in Gallipoli, but now they collect four akçes from each of us. Also, the Salatin Imarets (charitable kitchens) in Bursa and certain prominent figures used to have an annual allocation of sixty thousand sheep exclusive to Bursa. Now, these shares have become state property. Another reason presented was an official decree shown by the butchers. This decree stated that when the price of mutton in the blessed city of Islambol (Istanbul) was set at 350 dirhams, it should be set at 300 dirhams in Bursa; and if it was 300 dirhams in Istanbul, it should be 250 dirhams in Bursa.

Market Vendors: When the market vendors, along with their expert assessors and other townspeople, were gathered and asked about the old regulations concerning fruits, they said: In the past, whatever type of fruit arrived at the market, both townspeople and vendors could buy it freely as they wished. But for the past four or five years, vendors have united and begun to collect all fruits brought into the city, as well as those from surrounding vineyards, orchards, and shops. They store them and, with the agreement of the mayor, set fixed prices for each type, recording these in the court registers. However, they also sell part of their stock outside the official market at their own discretion and share the profits with the mayor. This was their testimony. When the truth of the people’s claims was confirmed, the registers were reviewed, and to investigate further, some fruits were brought from the market and examined. The regulations were found to be as follows:

Fruits:

- Cherries: Initially, 150 dirhams were sold for one akçe. After three days, the price changed to 200 dirhams for one akçe. Later, 250 dirhams for one akçe. After every three days, the quantity sold for one akçe would decrease by 100 dirhams, until eventually, one okka (a larger unit) would be sold for one akçe.

- Fresh Apricots: Initially, 200 dirhams were sold for one akçe. After three days, 300 dirhams would be sold for one akçe. Thereafter, depending on supply, prices would be adjusted according to this pattern.

- Fresh Plums: Initially, 200 dirhams were sold for one akçe. After three days, 500 dirhams, and then 600 dirhams would be sold for one akçe, continuing in this pattern until the season’s end.