Collective housing specific to the Jewish diaspora is one of the accommodation methods developed by a community facing exile pressure, shaped by the experiences gained across different geographies. The Jewish exile and mass Jewish migrations, which resulted in intensive Jewish settlement in Anatolia, took place over three distinct periods under different conditions. The first was the great Jewish exile that began in the 8th century BCE and evolved into a total migration by the 6th century CE. The second consisted of the Sephardic exiles (Jews of Iberian origin), which essentially started in 1390 and peaked between 1492-1497. The third was the Ashkenazi migration from Russia and Poland that began in 1881. Living in continuous exile for twenty-eight centuries endowed the Jewish nation with significant experience regarding migration and life in exile.

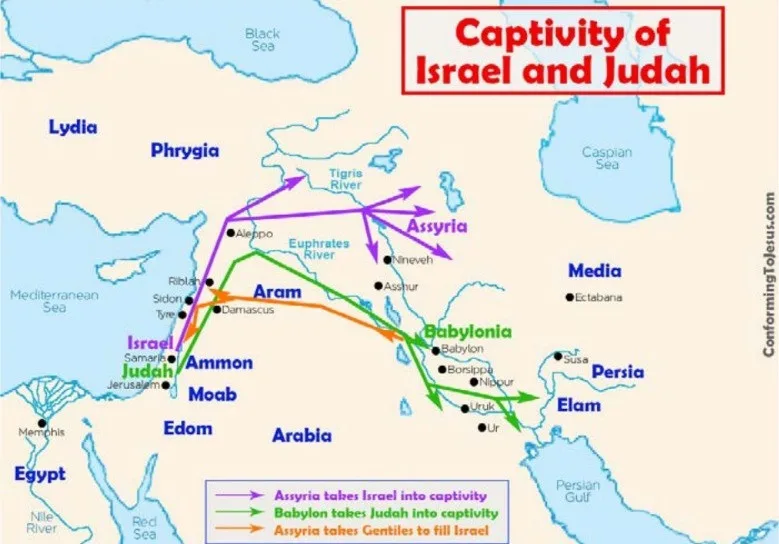

A map showing Jewish migration and exile movements between the 6th century BCE and 1650 CE.

The term diaspora, derived from the Greek verb diaspeiro (διασπειρω = to scatter), first appeared in the Septuagint (the earliest Greek translation of the Torah) in Deuteronomy 28:25: “The Lord will cause you to be defeated before your enemies. You will come at them from one direction but flee from them in seven, and you will become a thing of horror to all the kingdoms on earth.” The Hebrew equivalent of diaspora is pezura (פזורה: dispersion, scattering). Pezura is used in Jeremiah 50:17: “Israel is a scattered sheep…” However, pezura did not convey the combined meanings of dispersion, scattering, evoking fear, the fear of not being able to settle permanently in the host country, and exile. Therefore, in Jewish oral tradition, the term galut (גלות = exile) was preferred to describe the Jewish diaspora, as it encompassed all those meanings. On the other hand, after the Babylonian Exile, the term tfutsot (תפוצות = diaspora) also began to be used to refer to Jews dispersed to the four corners of the world. In fact, in Israel today, the term tfutsot is used to describe the diaspora.

The Hebrew Nation’s First Encounter with Migration

The Torah is the sole primary source regarding the ancient history of the Hebrew nation (the Israelites). According to the narratives and legends in the Torah, the history of the Hebrews begins with migration. Abraham was born in Ur of the Chaldeans. In the first half of the 20th century BCE, he left Ur with his family and came to Haran: “Terah took his son Abram, his grandson Lot, son of Haran, and his daughter-in-law Sarai, the wife of his son Abram, and together they set out from Ur of the Chaldeans to go to Canaan. But when they came to Haran, they settled there.” (Genesis 11:31). Around the 14th century BCE, under Moses’ leadership, the Hebrew nation left Egypt and settled in the Promised Land under Joshua’s leadership, forming twelve tribes. Over time, they transitioned from tribal governance to monarchy. The kingdom expanded and strengthened during David’s reign. After Solomon’s death, the kingdom split into two. Ten tribes formed the Kingdom of Israel in the north, while the remaining two tribes, Judah and Benjamin, continued as the Kingdom of Judah. The Kingdom of Israel in the north was later conquered by the Assyrian Empire.

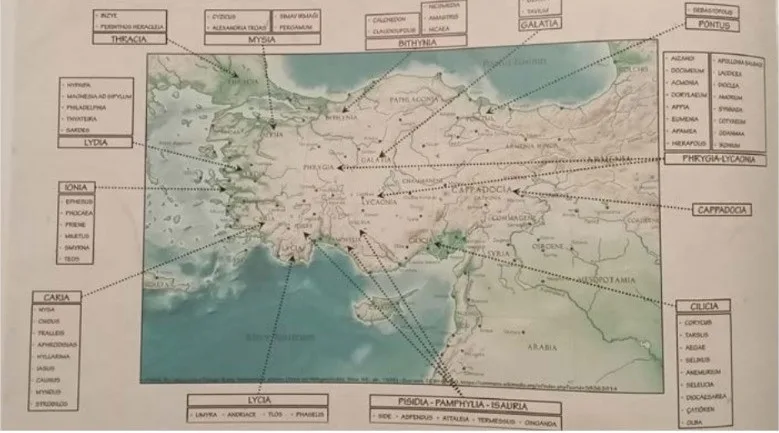

Assyrian King Sargon II exiled 27,290 Israelites to Assyria: “They were settled in Halah, on the Habor River of Gozan, and in the towns of the Medes.” (2 Kings 17:6). Halah was in Assyria, Gozan was on the Habor River in modern-day Syria, and the Medes lived in Hamadan, Iran. This took place in 722 BCE. The first diaspora dispersed almost the entire Middle East. Sargon II’s own records mention thirty-eight different exiles, from which it’s understood that the Assyrians treated the exiles harshly. Even today, debates persist regarding the fate of the ten Israelite tribes: Were all ten tribes present when the Kingdom of Israel fell? Did those exiled assimilate into the societies they joined, or did they preserve their faith, culture, and identity? The Kingdom of Israel had strong commercial networks. Among those exiled by the Assyrians, did any continue these networks and settle in new trade centers? When the Assyrian Empire fell, did any exiled Israelites return to settle in the Kingdom of Judah? There is also debate over how far these exiles may have traveled over the years: possible locations include Khorasan, Samarkand, Crimea, China, India, Africa, and Anatolia.

A map showing the invasions of the Israel and Judah kingdoms by the Assyrian and Babylonian empires and the directions of Jewish exiles.

The Babylonian Exile

The Assyrian Empire didn’t last long, ending in 612 BCE, replaced by the rising Babylonian Empire. The Kingdom of Judah in the south was invaded by Babylon. The Babylonian army burned the temple, palace, and homes of Jerusalem. Solomon’s Temple was destroyed in 586 BCE. Most survivors were exiled to Babylon, except for some of the poor, left to work the fields and vineyards in areas like the Negev Desert, Galilee, and Gilead. This event scattered the Jewish diaspora across Mediterranean countries. The first and second exile groups sent to Babylon included political, military, and religious leaders, as well as wealthy professionals and skilled workers. In exile, they found themselves within one of the world’s most advanced civilizations. They were just one of the many nations of the Babylonian Empire;a cosmopolitan society whose capital, Babylon, was an international metropolis. They built new lives and businesses and grew wealthy over time.

When Babylon fell to the Persians, their captivity ended. However, many chose not to return to Jerusalem, unwilling to abandon their new lives and property. The Babylonian Empire, spanning from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf, controlled key trade routes such as the Incense Route between Yemen and Western Arabia, and the Mediterranean ports between Gaza and the Gulf of Alexandretta. Fearful of losing control of East-West trade, Babylon likely sought to utilize the commercial expertise of the Jewish merchants, probably granting them trade privileges. This enabled Jewish merchants to strengthen their international trade ties with Anatolian cities, known to them since Solomon’s trade fleet days. Anatolia, rich in surface and underground resources, was a valuable peninsula at the time. Information exists regarding Jews sold as slaves as well. Joel 3:6, believed to date to the 6th century BCE, states: “You sold the people of Judah and Jerusalem to the Greeks, that you might send them far from their homeland.” If this date is correct, it suggests that Jews reached Anatolia not solely for trade, but also through enslavement.

Life in Exile During the Persian and Hellenistic Periods

Persian rule in Anatolia lasted over two centuries, from Cyrus’s conquest of Western Anatolia until Alexander the Great crossed the Dardanelles. Jews who chose to remain in Babylon likely benefited from the trade route stretching from Susa (Shush city) to Ephesus alongside the Persians, and probably settled in ancient cities along the Royal Road to maximize commercial gain.

According to one claim, when Alexander reached Jerusalem, he exiled several hundred Jews to Smyrna (modern-day İzmir). Another claim suggests he brought some Jews to İzmir on his return from Jerusalem in the 3rd century BCE. After Alexander’s death, Seleucid King Antiochus III established good relations with the Jews of Jerusalem and its surroundings. In fact, due to his trust in the Jewish community, when uprisings broke out in Lydia and Phrygia, he settled 2,000 Jewish families (approximately 10,000 people), drawn from loyal, soldier-based families from Mesopotamia and Babylon, in these rebel regions. Thus, permanent Jewish settlements were established in Anatolia, and from this point on, Jewish presence in Anatolia continued uninterrupted.

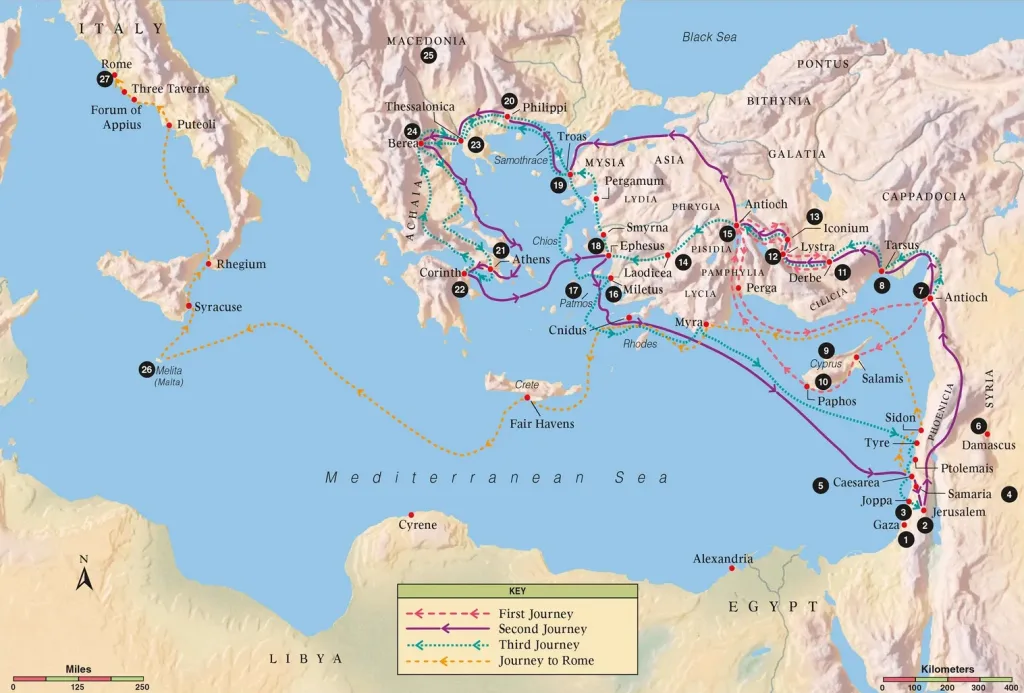

A map showing Jewish settlement locations in Anatolia by region during the Roman Period (from Jewish Identity Etched in Stone, 500th Year Foundation Turkish Jews Museum Publication, Istanbul 2021).

The Roman Period

Rome’s conquest of Anatolia began in 188 BCE, and by 129 BCE, Anatolia was under direct Roman control. By the 2nd century BCE, it’s estimated that Jews lived in over fifty Anatolian cities. Babylonian Talmud references confirm Jewish communities in Nisibis (Nusaybin) and Caesarea Mazaca (Kayseri) under Roman rule. Rabbi Judah ben Bathyra, estimated to have lived around the time of Rabbi Akiva, was from Nisibis. He was head of the Bet Midrash (house of study) in the city, where notable scholars like Rabbi Eleazar ben Shimon and Rabbi Yohanan HaSandlar studied. His fame even reached Jerusalem: “Peace be upon you Rabbi Judah ben Bathyra, your fame and influence in Nisibis have spread to Jerusalem.” (Babylonian Talmud, Pesachim 3b). In the same period, a Jewish community existed in Cappadocia: “Rabbi Yohanan ben Nuri stood and asked aloud: What will those in Cappadocia burn for light on the Sabbath? They have neither radish oil nor pistachio oil. Will they burn mineral oil?” (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 26a). In the mid-3rd century CE, 12,000 Jews in Caesarea Mazaca, the largest city of Cappadocia, were killed by Sasanian King Shapur I (Babylonian Talmud, Moed Katan 26a).

Jewish communities in Anatolian cities were also mentioned in letters from the Roman Senate, granting privileges to Jewish communities, and in legal documents recognizing their rights. Letters from the Senate to the kings of Pergamon and Cappadocia and cities like Myndos, Halicarnassus, Cnidus, Phaselis, and Side recorded Rome’s support for Jews.

Another indicator of Jewish presence in Anatolia during Roman times is tied to Paul’s missionary journeys. The primary geographical area where Paul spread his interpretation of Jesus Christ was Anatolia. He often visited cities with significant Jewish populations, preaching in their synagogues. Thus, tracing Paul’s route helps identify Jewish settlements in Anatolia.

The routes followed by Paul during his missionary journeys in Anatolia and the Balkans.

Cultural Diversity of Diaspora Jewish Communities

The first challenge Jews faced in exile was statelessness. In host countries, Jewish migrants or exiles, encountering legal obstacles, tolerance, or persecution, often had to repeatedly prove their trustworthiness to gain a foothold and, ideally, citizenship. Over time, sometimes by necessity and sometimes by choice, they absorbed and integrated local cultural elements. In every geography and country, Jewish communities emerged, blended with local cultures. Nevertheless, their collective memory and consciousness distinguished the Jewish diaspora. They lacked a homeland but maintained belief in the Messiah and eventual return. However, fears of losing a common Jewish identity led religious leaders to initiate measures: starting with emphasizing family and lineage ties and later developing complex structures over centuries.

Religious organization began during the Babylonian Exile and continued in the Second Temple period. The Sanhedrin, the Jewish religious court that launched the interpretive tradition aiming to reveal the secondary meaning behind the Oral Torah, emerged in this period. Scholars in religious academies in Jerusalem and Babylon shaped Jewish oral tradition into the written Talmud and initiated the regular synagogue worship tradition. The establishment of Jewish social institutions in the diaspora aimed to preserve language, religious values, social norms, homeland narratives, and limit interaction with other groups, ensuring the continuity of the Jewish people as a religious and ethnic community. In each city with Jewish populations, synagogues, schools, cemeteries, social institutions, ritual baths (mikvahs), kosher food shops, butchers, and social housing (known as Yahudihane and Kurtijos) for especially poor Jewish migrants were established.

The Manisa Akhisar Hotel is the only remaining classic example of a Kurtijo in İzmir.

During the Ottoman period, scarcely any city in Anatolia lacked a settled Jewish community. By the 19th century, even small towns and villages were added to this network. Given the scope, I will explain the cultural diversity of Jewish communities in Anatolia mostly through the İzmir example. Wherever Jewish communities live, they expand and develop through migrations, or conversely, diminish or vanish due to them. The city of Smyrna (İzmir) also received waves of Jewish migration from antiquity. Initially, Romaniotes lived there. Later came Mizrahis from the Near and Middle East (likely Maaravi/North African and Musta’arabi/Yemenite Jews), followed by Central European Ashkenazim and Karaite Jews. Over time, all these early arrivals assimilated into the dominant Romaniote culture. Eventually, a large Sephardic group settled in the city. Significant numbers of Portuguese Converso (crypto-Jewish) migrants and the Frankos also arrived, leading to the formation of a Jewish community that far surpassed those in other Ottoman cities in size, wealth, and creativity. Over time, İzmir’s Jews adopted the rich Sephardic culture and became known as Sephardim. Even the latest Ashkenazi migrants from Russia and Eastern Europe eventually assimilated into this Sephardic identity.

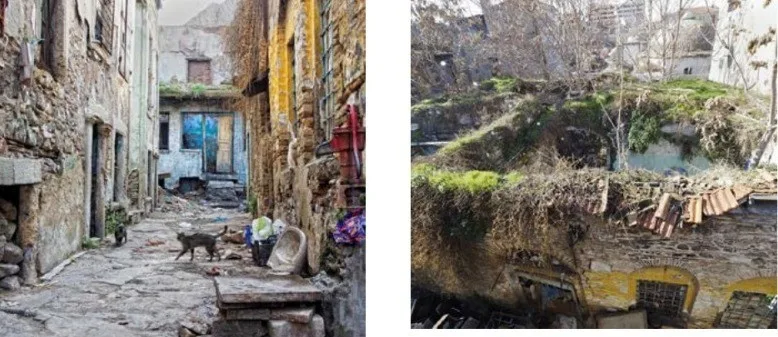

Aerial view of the old Hahamhane building, which also housed the İzmir Chief Rabbinate office.

Romaniotes

The Romaniotes were Jews who settled in Anatolia in antiquity and continued through the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The term Romaniot referred to Jews living in Constantinople, the Balkans, and Anatolia during the Byzantine Empire. Their personal names (Yosef/Iosefus/Ιοσεφυσ) and synagogue names (Eklesia/Εκκλησια) were in Greek. Especially in Istanbul, their numbers were high. Many of their prayers and rituals were compiled in the Hebrew-Greek Mahzor Romania. The language they used was not Aramaic or Hebrew but Greek, often called Judeo-Greek today: a blend of Hebrew and Greek. Their community organization, dating back to the 6th century BCE in Anatolia, was used by Ottoman Jews until the 17th century. This structure, akin to a feudal system, was similar to that used by Jewish communities in Islamic countries since the Middle Ages. From the 17th century, Ottoman Jewish communities adopted the Iberian model, forming flexible religious community structures within cities to meet basic religious needs.

Mizrahim (Maaravim and Musta’ribun)

Jews from the eastern regions, known as Mizrahim, also settled in Anatolia. While they primarily migrated to the eastern and southeastern cities, some also moved to Izmir and Istanbul. For Jews who were closely involved in every branch of commerce, port cities with intense commercial activity were centers of attraction. It is likely that among them were Jews of North African, Safed, Baghdad, and Yemeni origin. Therefore, those who arrived were Jews who had adopted Arab culture and spoke Arabic. I will provide an example regarding this: At the beginning of the 1590s, Rabbi Yomtov Tzahalon, who came to Izmir from Safed, spoke of the Jewish presence in the city. He was consulted regarding the marriage of a widow named Afiya and a man named Nojim, son of Süleyman. This community, which had not yet formed an organized congregation, had neither a rabbi, nor a leader, nor any laws (takkanot). Names like Afiya and Nojim were not used in Anatolia. However, such names were common in Arabic-speaking regions. Both individuals mentioned were likely Jews originating from Safed, Baghdad, North Africa, or Yemen.

Before and after photos of the İzmir Hevra (Talmud Tora) Synagogue renovation.

Karaites (Karaim)

This community, which emerged in the 8th century in Baghdad, is a sect of Judaism. They believe only in the Torah and no other books. Their name derives from the Hebrew word kara (to read), meaning “those who read.” This community, which concentrated and grew in the region until the 9th century, later migrated to Constantinople (Istanbul), Alexandria, and Jerusalem. They expanded and developed during the Byzantine period. No specific sources mention their arrival in Izmir or the reasons for it. Only one source references the presence of Karaites in Izmir in the 17th century. In Istanbul, however, they have continued to exist as a fairly large community up to the present day.

Sephardim

One of the leading scholars of 15th-century Iberian Judaism, Rabbi Don Isaac Abarbanel, wrote that after the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar destroyed the First Temple, Jews were taken to Spain as slaves. The earliest documented history of Spanish Jewry dates back to the time when the Romans destroyed the Second Temple in Jerusalem and took tens of thousands of Jews to Europe as slaves, some of whom settled in Spain. A tombstone found in Adra, in southern Spain, in 1783 dates back to the 2nd century AD. The inscription on the tombstone mentions the name of a child, though much of the name is erased: “Daughter of Solomon, a Jew, who died at one year and four months old.” Although little is known about these early Jewish settlements, sarcophagi in the Tarragona necropolis reveal that a Jewish community lived in Roman Spain from around 200 AD onwards.

It is helpful to examine Sephardic migration to Anatolia in two distinct groups. The first group consists of those who settled in Anatolia after being expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in the period of 1492/97. The second group includes Jews who were forced to leave Spain and Portugal in 1492, 1497, and 1540, and who settled in a broad geographical area stretching from the North African coasts to the Middle East, and from Northwestern Europe to the Mediterranean Basin. Although some among them preferred to migrate directly to Anatolian cities, their numbers were fewer compared to the first group. Countries such as the Netherlands, Marseille, the city-states of Northern and Central Italy, Naples, Rome, and Papal principalities treated Jews relatively amicably, provided they paid taxes and did not disrupt public order. On July 10, 1593, Ferdinand, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, declared the city and port of Livorno a free zone. Ferdinand also promised significant rights to the diaspora Jews: protection from all persecution (especially the Inquisition), amnesty for crimes allegedly committed in other countries prior to arrival, tax exemptions, voting rights, and most importantly, the right to freely practice Judaism in society without fear of attack. Many Jews, living in fear of Christian persecution and the Inquisition, preferred to migrate to Livorno. For Portuguese Jews, Amsterdam became the center in Northern Europe, while Livorno became the center of Southern Europe. The Grand Duke Ferdinand consciously invited Portuguese and Spanish Jews, who until then had been residing in nearby city-states, principalities, and Papal territories, to settle in his lands. Among those who responded to the invitation were Portuguese Jews (Conversos) who had previously resided in Ottoman cities and had reverted to Judaism, as well as old Portuguese Jews/New Christians. The main cities where Portuguese Jews settled within the Ottoman borders were Istanbul, Thessaloniki, Edirne, and Safed. Thessaloniki was the most preferred city. Here, they integrated with the Francos community, eventually joining their congregation. The Francos were Jews who had settled in Marseille and Bouillon after leaving Portugal in 1497 and 1540. After living in these two cities for several generations, they migrated to Ottoman lands, particularly Istanbul, Thessaloniki, and Izmir.

In the 19th century, a new classification was introduced for Ottoman Jews. Sephardim who, after expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula, settled in major cities of Western and Central Europe such as Hamburg, Amsterdam, and London, and did not leave those cities, were defined as the Western Sephardic Diaspora. Those who, after leaving the Iberian Peninsula, either migrated directly or after a short stay in other European cities, settled in cities within the Ottoman Empire, and by the 19th century were socioeconomically and culturally far behind the Western Sephardic Diaspora, were labeled as the Eastern Sephardic Diaspora.

Izmir Neve Shalom Synagogue

Ashkenazim (Ashkenazi Jews)

These are Israelites who were exiled by Rome, particularly after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD, to Central and Eastern Europe. Their language is Yiddish. This term also began to be used for Jewish settlers who lived in Western Germany and Northern France during the Middle Ages and established settlements along the Rhine River. In the Late Middle Ages, due to antisemitism and discrimination, the majority of Ashkenazi Jews continuously migrated eastwards, into the lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which included parts of present-day Belarus. They spread throughout this region and contributed significantly to Europe’s commerce, philosophy, literature, art, music, and science.

Ashkenazi migrants who came to Anatolia should be evaluated in two different categories: the first group were of German/Austrian and Central European origin, while the second group were of Russian and Polish origin. Accordingly, the synagogues and community organizations of German Jews settled in Izmir were different from those of Russian and Polish migrants.

Rozanes indicates the reign of Murad II (1421–1451) as the beginning of Ashkenazi settlement in Ottoman lands. A possible increase in Ashkenazi settlers likely began in 1470, when the Kingdom of Bavaria expelled its Jews. However, Rozanes’ information relates specifically to the city of Istanbul. In Izmir, evidence of Ashkenazi presence in the 17th century is scarce. Rabbi Eliyahu HakohenItamar wrote that when he arrived in Izmir, he encountered educated and cultured Ashkenazim. Yet apart from his memoirs, there is no concrete data indicating whether Izmir received Ashkenazi migration specific to the 15th century.

The migration of Russian and Polish Jews to Anatolia began in the second half of the 19th century. Particularly in this period, anti-Jewish developments in Russia, Germany, and Romania forced Jews who had lived in these countries for centuries to migrate. Jews living in Russia faced discriminatory and restrictive treatment from 1791 onwards. Between 1791 and 1881, Russian Jews lived a partially free life, but this so-called freedom ended entirely after the assassination of Alexander II. From 1881, pogroms targeting Jews began in Russia. The policy of Tsar Alexander III to create a Russian Orthodox nation forced Russian Jews to choose between Russification or migration. Some of those who left Russia and came to Anatolia settled permanently in cities with significant Jewish populations like Izmir, Istanbul, and Thessaloniki. Those who temporarily settled in these cities stayed in hostels or synagogues before preferring to migrate to Palestine. Those who remained in major cities were generally poor. Some were directed towards agricultural activities, but harsh conditions in rural areas made life difficult for families with children. Very few families continued in agriculture; others returned to the cities.

Migrant Housing (Kurtijos and Yahudihanes)

Collective housing structures known as Kurtijos and Yahudihanes, specific to the Jewish diaspora, were developed over centuries as a method of shelter by a community that had faced exile pressures since the 8th century BC and collectively from the 6th century BC onwards. These structures represent the sociological and architectural reflections of the practical mindset of the Jewish diaspora, accustomed to migration. In cities they moved to, they created building complexes in narrow areas allocated to them, accommodating as many families as possible while meeting their needs for security, water, food, and worship.

Jewish quarters known as İzmir Taş Kurtijo

Kurtijo is a Spanish-derived word meaning farmhouse in rural areas. In Ladino, however, Kurtijo refers to a courtyard or patio. This meaning and its related use are unique to Ottoman Sephardic Jews. The origin of Kurtijos should be the Middle East. After the destruction of the First Temple in the 6th century BC, a segment of the exiled diaspora Jews settled in the Iberian Peninsula, likely bringing the concept of collective housing to that region as well. The common features of Kurtijos are large entrance gates opening to wide courtyards. Mediterranean climate features are prominent, and spatial organization is influenced by Mediterranean design. The use of open space is particularly important. A water source and citrus trees are found in the courtyard’s center. Around the courtyard, two- or three-story buildings consisting of small 8-10 square meter rooms and corridor-like galleries are constructed. Rooms lack sinks, baths, and toilets. Shared facilities in the courtyard -such as toilets and wells (fountains or pumps)- serve all the residents’ needs (washing, cooking, laundry). Today, the Manisa Akhisar Hotel in Izmir remains an ideal example of a Kurtijo.

In contrast to Kurtijos, Yahudihanes have different architectural features and are called dirot (apartments) in Hebrew. These consist of small adjacent apartments or detached houses, sometimes resembling train cars lined up side by side. Only one part of each home has a small kitchen area. A narrow street typically runs through the center of the complex. In years when large numbers of Jewish migrants arrived in the city, architectural additions were made to these buildings to meet urgent housing needs, giving each Yahudihane a distinct appearance. Depending on the arrangement around the central street, Yahudihanes could be I-shaped, U-shaped, or T-shaped with a common street and courtyard. Some Yahudihanes developed around an organically formed street pattern, where independent yet adjacent houses collectively formed a large settlement. The street widened at certain points to create small seating areas shaded by citrus trees. Paşa Yaakov Yahudihane (Cevahir Han) is the only example of this formation.

In Izmir, Yahudihanes were built from the 1590s onward, when Jews first settled there, possibly even earlier during the Byzantine period. Kurtijos began to be constructed with the arrival of Iberian Jews in the early 17th century. The numbers of both building types increased rapidly from the 18th century onwards, in direct proportion to the rising Jewish migrant population. Particularly from the 18th century, the mass arrival of impoverished Jews brought a housing crisis. In the Ottoman period, Anatolian cities were divided into neighborhoods based on the religious and ethnic identities of their inhabitants. This was to facilitate security control by the Ottoman administration. Thus, each community remained within designated areas, although this separation did not amount to a strict ghetto system. In Izmir, the Jewish Quarter was bordered by Armenian and Muslim neighborhoods on one side and the Kemeraltı Bazaar on the other, limiting its expansion. Consequently, the neighborhood expanded internally, leading to either the construction of more Kurtijos and Yahudihanes or architectural additions to existing structures, creating diverse Jewish social housing units.

Until now, I have discussed Jewish migrants arriving in Anatolia from the Mediterranean Basin, Europe, the Middle East, and Russia. Additionally, there were periodic and intense Jewish migrations between Anatolian cities themselves. To better understand these migrations, it is useful to examine Anatolian Jews in the context of the Ottoman bureaucracy’s relationship with its non-Muslim subjects, social needs, traditions, political events, natural disasters, security concerns, and the rights and obligations introduced by the Republic of Turkey.

Family ties, freedom of movement, natural disasters, political developments (wars, uprisings, exile, security concerns, expulsion), the pursuit of new opportunities, typical migrant indecision, and economic uncertainty can be cited as main reasons for Jewish migrations.

During the Turkish Republic era, between 1922 and 1924, in 1928, 1934, 1942, 1948, and 1955, mass migrations occurred as Jews who had lived in Anatolia for centuries left for America, Australia, Europe, Africa, and the newly founded State of Israel. One may ask: was Anatolia still an attractive geography for communities of different religions and ethnicities? Was it still receiving migrants? If so, what were the religious and ethnic backgrounds of these migrants? Were there Jews among them?

In 2002, the US-led invasion of Iraq marked the beginning of major changes in the political, social, and strategic structure of the Middle East. Wars and subsequent occupations in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Syria forced millions of Muslim and Christian families to migrate to Anatolia, seeking a safer environment and better social and economic conditions. Some of those who came to Anatolia settled permanently, while others used Anatolia as a transit point en route to Europe and the Americas. Many families in Israel either directly affected by the attacks or fearing missile strikes left Israel as well. While some migrated to cities in Europe and the US, others came to Anatolia. Considering that, in addition to Jewish families settling in or transiting through Anatolia, many Palestinian families fleeing the heavy Gaza bombardments also settled in Anatolia, we can say that the 21st century has gone down in history as an age of migrations and migrants. Anatolia continues its age-old role as both a sanctuary and a bridge.