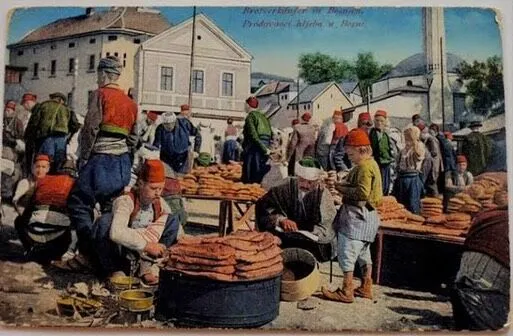

Istanbul, as the capital of the Ottoman Empire, had grown into a densely populated city. Wars, migrations, and the concentration of soldiers and bureaucrats significantly increased the demand for bread, making the establishment of bread factories a necessity.

Bread is one of the oldest, most fundamental, and essential food items known to humanity. During the Ottoman period, the need for bread in Istanbul was of great importance. Due to wars, migrations, and other reasons, by the first quarter of the 20th century, Istanbul’s population had surpassed one million. Meeting the bread needs of such a large population was a critical challenge, as bread was the main staple food of the city’s inhabitants. The migrations triggered by the 1878–1879 Russo-Turkish War and the Balkan Wars had further amplified the demand for cheap bread. In addition to this, the city housed a significant bureaucratic and military class.

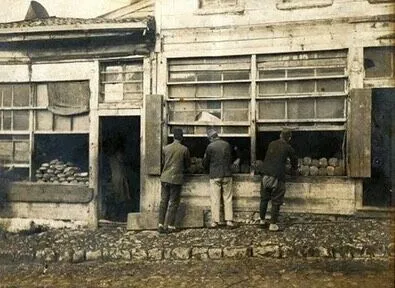

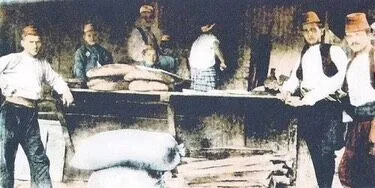

Traditional mills and bakeries lacked the capacity to address the growing bread shortage. Therefore, modern bread factories and mills, adhering to European production standards, needed to be established. Work accelerated, and modern bread production facilities began to appear in Istanbul. The Ottoman State launched its first bread production plant by founding the Nişantaşı Bread Factory.

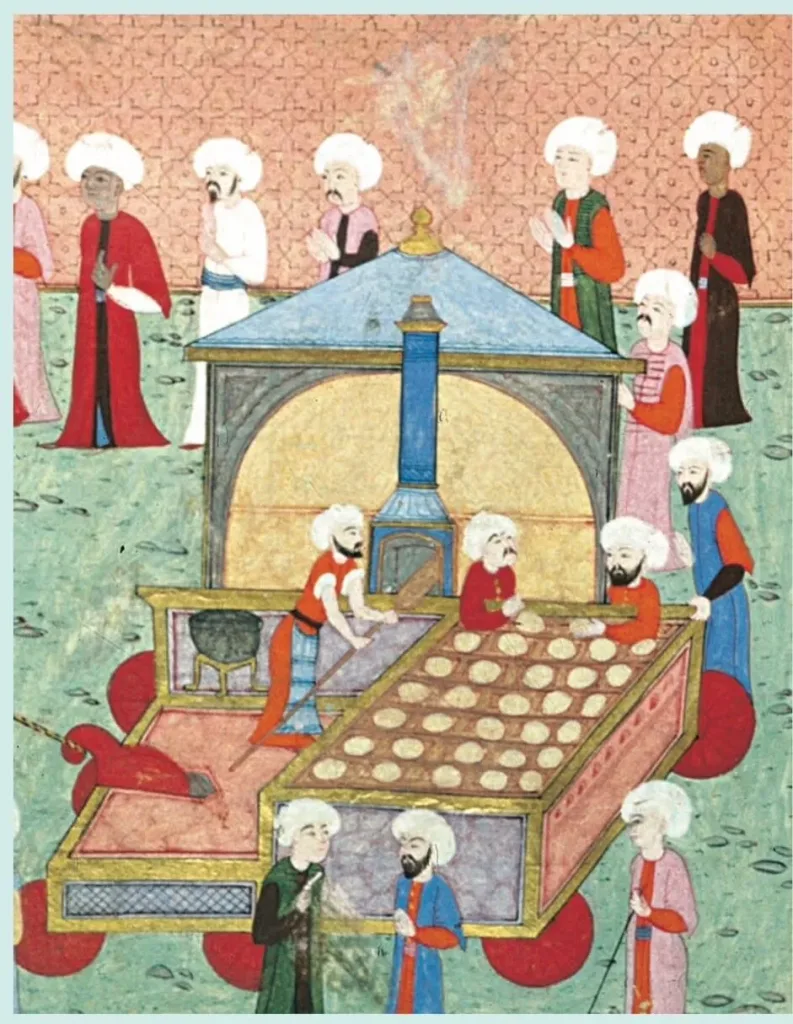

Under the Sultan’s Supervision

Strict monitoring mechanisms were put in place to ensure Istanbul’s population could consume affordable bread made from high-quality wheat. Since bread was the people’s primary food source, the Sultan, Grand Vizier, and other state officials maintained tight control over bakeries.

To manage the production and distribution efficiently, joint-stock companies began to emerge. One such company was the “Ekmek ve Ma‘mûlât-ı Dakîka Şirket-i Osmâniyesi” (Ottoman Bread and Flour Products Company), which aimed not only to produce bread but also to manufacture and sell baguettes, biscuits, pasta, cakes, chocolate, and various other flour-based products.

The World’s First Food Standard

Since its foundation, the Ottoman State had shown particular sensitivity to bread production. Each Sultan paid special attention to this matter. According to historical sources, the Ottoman Empire was the first to introduce a food standard in the world. This law was the “Kanunname-i İhtisab-ı Bursa”, enacted in 1502 during Sultan Bayezid II’s reign. Recognized as the world’s earliest written document establishing standards in the modern sense, it set regulations regarding quality, size, packaging, price controls, and penalties. The law even specified the exact weight of loaves and the amount of sesame to be sprinkled on top. Violators faced serious penalties. This regulation was enforced not only in Bursa but throughout the Ottoman Empire.

After the conquest of Istanbul, Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror appointed Hızır Bey Çelebi as the city’s first mayor. His first directive was to ensure bakeries maintained strict hygiene standards, banned adulteration of dough, and produced bread that met public satisfaction.

A 1680 guild regulation prepared by the Istanbul Kadı (judge) stipulated a fine of one akçe for producing undercooked, burnt, sour, or insufficient bread and pastries. Furthermore, sieves in bakeries had to be tightly woven, and bread was forbidden to contain bran.

No Bakery Without a Guarantor

Strict laws required anyone wishing to work as a baker to provide a guarantor. Without one, no bakery could operate. Guarantors were held responsible for any violations. Bakers could not simply abandon their profession at will; they could only transfer their bakery license to someone else in the presence of a judge. A baker was also forbidden from shutting down their bakery under any circumstance. Punishments were harsh: bakers who produced undersized loaves were not only fined but could also be nailed by the ear to their bakery wall or beaten publicly with a stick.

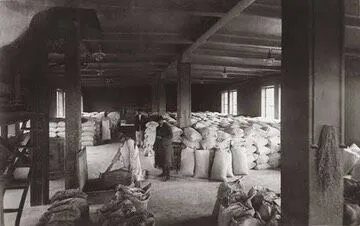

Wheat Came to Unkapanı

Wheat, the primary ingredient of bread, remained under state monopoly during the Ottoman period. Securing enough wheat and flour for Istanbul’s daily bread consumption was among the state’s most critical tasks. Wheat was stored in state-owned granaries, and its sale price was set by the government.

The district known as Unkapanı derived its name from the words “un” (flour) and “kapan,” which referred to a wholesale marketplace in Ottoman times. Ships bringing grain to Istanbul would unload their cargo at Unkapanı. The official known as the “Un Emini” (Flour Overseer) was stationed at Unkapanı. Flour required by soup kitchens, scholars, military barracks, and urban bakeries was supplied from there.

Failed Attempts

In response to Istanbul’s growing bread needs, the Ottoman State sought to establish bread factories. The first attempt was to build one in Haydarpaşa, and Muhiddin Bey, an official from the Ministry of Interior, was tasked with the project. Despite placing machinery orders from Europe and completing other necessary steps, the factory was never opened, and the project was canceled.

Nişantaşı Bread Factory

Soon after, Artin Arslanyan applied for permission to open a bread factory. With state approval, he founded the “Arslanyan Ekmek ve Mamulât-ı Dakikiye Şirket-i Osmaniyesi” in 1912. After importing machinery from Vienna, the first bread factory of the Ottoman Empire was established in Nişantaşı, at a site known as Taşocağı. The Nişantaşı Bread Factory could produce 30,000 loaves of 720 grams each per day.

Later, the Nimet Bread Factory was opened in Unkapanı. These developments significantly alleviated Istanbul’s bread shortage.