One of the many ways people have expressed their aesthetic sense throughout history is through the art of mosaic. Mosaic art involves decorating surfaces by assembling small pieces of different colors and shapes. The history of mosaics stretches back to ancient times. In the Sumerian city of Uruk, wall coverings resembling mosaics from the 3rd millennium BCE have been found. One of the earliest known mosaics, dating to the 8th century BCE, was created from pebbles.

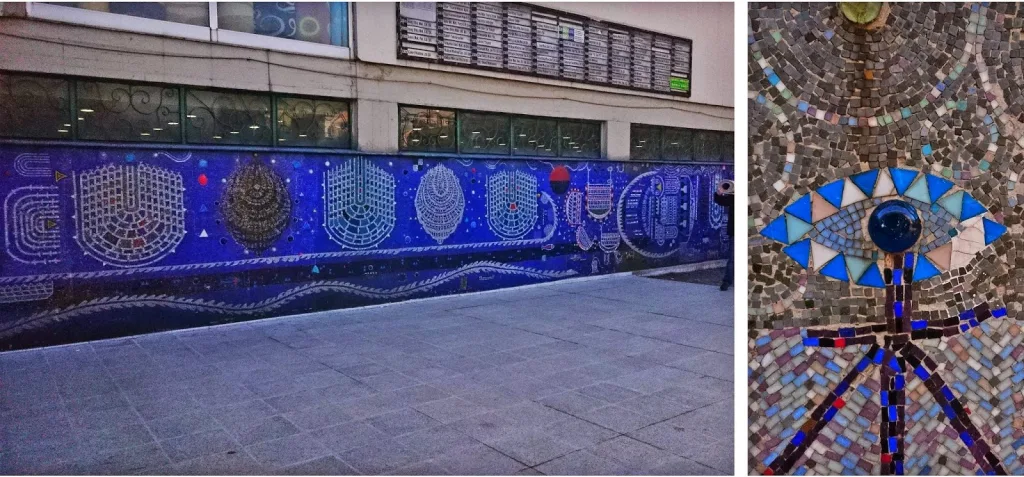

“Istanbul”, with its minarets and domes, Bedri Rahmi… The architecture of the IMÇ buildings was determined through a competition. The artists who would design the artworks to integrate with the architecture were also selected through an invited competition. We owe the mosaics of Bedri Rahmi and Eren Eyüboğlu to this competition.

During the Roman Empire, mosaics made primarily of glazed ceramics were used extensively on city pavements, house courtyards, and public squares. In Roman culture, such surfaces were preferred in luxurious villas to avoid mud formation on wet floors, helping people to cool down. As a result, mosaics became widely used in floor coverings and sparked greater interest in mosaic art among the elite. The mosaics excavated from the villas in the ancient city of Zeugma are among the finest examples of this era, now displayed at the Gaziantep Archaeological Museum.

The background of Eren Eyüboğlu’s mosaic panel at IMÇ and Bedri Rahmi’s “Ox Cart” panel at Tatlıcılar Bazaar is made of golden mosaic stones. However, the Betebe glass mosaic factory, established in Turkey in the 1950s, has been unable to produce the ideal bright carmine red and gold mosaic.

Evolution of Mosaic Art: From Floors to Byzantine Walls

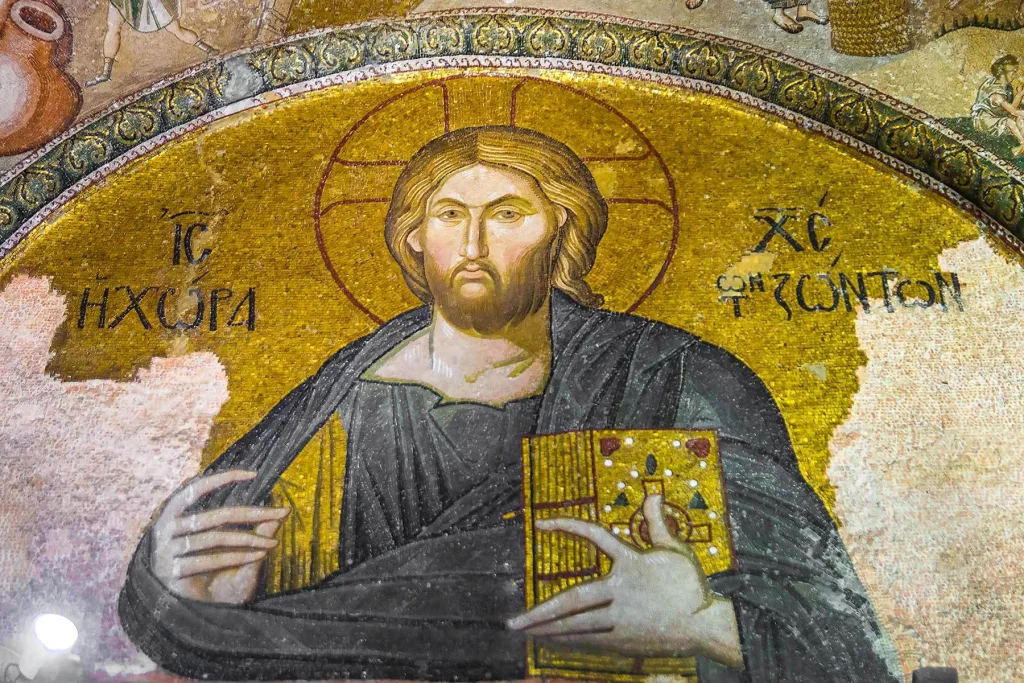

As mosaics became more colorful and varied in material, their use expanded. The period known as the Hellenistic Era (323 BCE – 146 BCE) saw the introduction of glass into mosaic art. Throughout the Byzantine period, glass became the primary material. During the Early Christian Era, metal leaf was applied over glass to create gold and silver tesserae, giving Byzantine mosaics their iconic appearance.

For the golden mosaic backgrounds and carmine red used in the panels by Eren Eyüboğlu and Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu at IMÇ and Karaköy, European stones left over from the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair and mosaics that Bedri Rahmi brought from Venice were used.

Istanbul: A City of Mosaics

Istanbul, having hosted many civilizations over centuries, reflects various artistic forms. Its structures, walls, and streets blend different cultures, keeping its spirit alive. Numerous mosaic works from the Byzantine period still survive in the city. These masterpieces have inspired countless artists and continue to shed light on contemporary art.

Mosaic art in Istanbul did not begin with modern artists. Many ancient mosaics can also be seen in the Chora Museum. Please visit https://en.kariyecamii.com/mosaics-and-frescoes

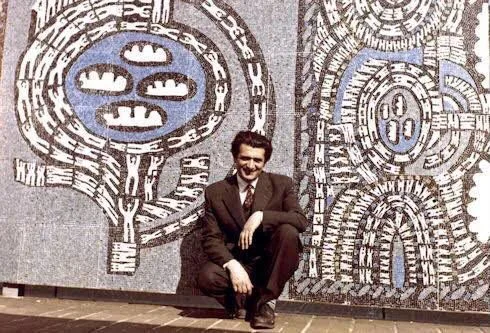

Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu: The Mosaic Poet of Istanbul

In the 20th century, Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu emerged as one of Turkey’s leading mosaic artists. In the 1950s, he became fascinated with Byzantine mosaics and began creating mosaic panels and murals inspired by them. Eyüboğlu embroidered Istanbul’s walls like lacework, leaving behind astonishing works that infused the city with soul. He reflected the Anatolian spirit in a modern and unique language, incorporating folk art figures and compiling his own symbols and motifs.

“Unless touched by the hand of an architect, a painting is doomed to a nomadic life; buried alive or put to sleep in dim museum halls.”

Unable to confine his art to galleries, Eyüboğlu used Istanbul’s walls as his canvas. His 227-square-meter work for the Turkish Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels International Exhibition and the mosaics he created with Eren Eyüboğlu at IMÇ (Istanbul Manifaturacılar Çarşısı) utilized European stones from the same exhibition and mosaics he purchased from Venice. Their background is made of golden mosaic stones, reflecting the Byzantine inspiration through a modernized and mesmerizing style.

Bedri Rahmi’s first wall mosaic was created for the Etibank Building (Ankara). It is now stored in a warehouse, waiting for the day it will be displayed.

In 1959, he also created a 50-square-meter panel for the Paris NATO Center and completed many works, especially in Ankara and Istanbul. Unfortunately, most of these works were not well preserved. Today, around twenty of his mosaic works in Istanbul are at risk of disappearing.

Disappearing Works: Lost in Restoration and Advertisements

Many of his site-integrated works have been lost due to restorations, signs, or advertisement panels. One example can be found in a delicatessen called “Özlem Sucukları” in Karaköy. The shop owner, who moved in during 1991, mentioned in an interview that the mosaics were accidentally discovered during renovations, as they had been previously covered.

Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu designed a mosaic panel for the NATO Headquarters in Paris, gifted by Turkey in 1960. Initially displayed at the Palais de l’OTAN, NATO’s first permanent headquarters, the mosaic was eventually relocated to the new headquarters in Brussels.

Sadly, this is not the only case. In recent years, the mosaic panel on the side facade of the Doğubank Business Center in Sirkeci was covered with insulation material during renovations. Four of his works in the 4.Levent Residences were concealed behind signage but later recovered thanks to an initiative by the Beşiktaş Municipality. Bedri Rahmi faced many challenges even during his lifetime but persisted with his productivity and passion for art, ensuring his works reached the present day. While similar obstacles persist today, Eyüboğlu’s creative drive, resilience, and dedication to art serve as enduring inspirations.

“I wanted to be the flame in the hearth of art…

Let me cry out on the horizon of art,

Either break my head,

Or break my brush.”

Bedri Rahmi, who blended Anatolia and the West, and the past of Istanbul in his heart, is one of the artists admired most—for his creativity, technical innovations, and tireless work ethic—but sadly, also one whose works have been most damaged.