One of the lesser-known stories of the conquest of Constantinople is the brave resistance of 300 Cretan warriors and how Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror allowed them to leave; a story truly worth reading.

Fatih Sultan Mehmed and His Respect for the Enemy

Fatih Sultan Mehmed… he was undoubtedly a commander who earned the title “Conqueror” through his rationality, scientific approach, and strategic thinking. One of his most important traits was never underestimating his enemies and always showing them respect.

Common Narratives of the Conquest of Istanbul

When it comes to the conquest of Istanbul, common narratives often take center stage:

- Fatih’s ships being hauled overland,

- Emperor Constantine XI’s heroic defense,

- Ulubatlı Hasan planting the first flag on the walls,

- Fatih charging his horse into the sea in anger at the Genoese escape,

- The massive cannons forged by Hungarian engineer Urban,

- Giovanni Giustiniani, the beloved Genoese commander defending the city.

However, on May 29, 1453, Emperor Constantine had fallen, and the widely celebrated Giustiniani had fled after being wounded. Turkish forces were entering the city from all sides.

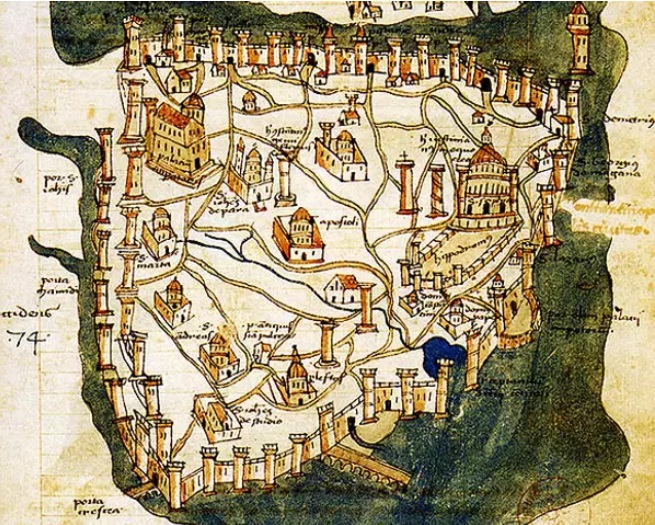

Resistance in the Shadows: The Three Towers

Despite the fall of the city, resistance continued near the Golden Horn in three towers: Alexis, Basil, and Leo. In these towers, 300 warriors stood firm. They were Sfakian warriors from Crete and had no intention of surrendering the city.

Who Were the Sfakian Warriors of Crete?

The Sfakians (Sfakyots) were descendants of the Dorian seafaring people who invaded the island in the 12th century BCE. Having endured many invasions themselves, they earned a reputation for being both stubborn and brave.

Though Crete was under Venetian rule in 1453, the region of Sfakia maintained semi-autonomous status. Led by Manousos Kallikratis, the region sent 750 warriors -including 300 Sfakians- and 3 ships to aid the Byzantine Empire in response to Emperor Constantine XI’s plea.

The Cretan Warriors Response to the Byzantine Call for Aid

As of April 6, 1453, the Ottomans had assembled an 80,000-strong force. Emperor Constantine could only gather about 7,500–10,000 defenders, including the Cretan troops.

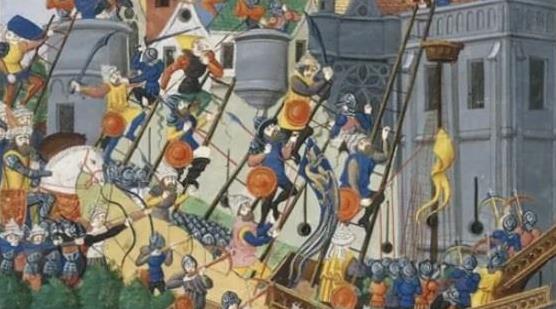

The Cretans fought bravely for the full two-month siege. Many were killed during the fighting. By noon on May 29, 1453, the city had largely fallen. But the Alexis, Basil, and Leo towers continued to resist.

The Final Stand: Alexis, Basil, and Leo Towers

The surviving 300 Cretan warriors withdrew into these three towers and mounted a fierce defense. Ottoman forces attacked but could not bring in their large siege cannons. Hours of assault failed to break the defense.

Eventually, the Ottoman pasha in charge of the siege offered the Cretans a chance to surrender with the promise their lives would be spared. The Cretans refused.

Meanwhile, Sultan Mehmed had already entered the city as the Conqueror and reached Hagia Sophia. He learned about the continued resistance in the towers near the Golden Horn.

Despite all efforts, Turkish forces were unable to defeat the Cretans in these final strongholds. Only 170 out of the original 300 warriors remained. Many Ottoman soldiers had fallen trying to break through.

Sultan Mehmed’s Offer to the Brave Defenders

The story of these brave defenders deeply moved Sultan Mehmed. He felt a reluctant admiration for their courage.

He sent word to them through a captured Byzantine commander. The Sultan’s decree read:

“Heroic Christian sailors, if you abandon the towers, you may take your weapons, banners, and belongings and sail back to Crete as invincible warriors. In addition, the Sultan’s personal guards will escort you to your ships, which will be provided to you. You will be saluted in friendship, and your lives will be spared…”

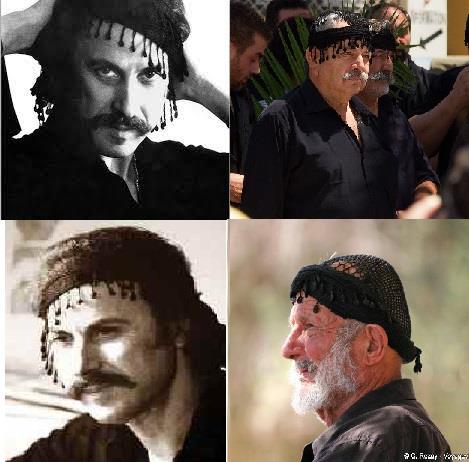

An Honorable Exit and the Birth of the Sariki

Just as Sultan Mehmed was a commander who respected his enemies, the Cretan warriors also held great respect for him and trusted his word. They surrendered, took their arms and banners, saluted the great Conqueror’s army, and boarded their ships from the Golden Horn.

Though praised even by their enemies as “invincible warriors,” they wore black kerchiefs on their heads to mourn the loss of Istanbul. This mourning headwear was called sariki.

From 1453 to WWII: The Enduring Legacy of the Sariki by Cretan Warriors

The sariki tradition, born in mourning after the fall of Constantinople, spread further after Crete came under Ottoman rule. It became a common item of cultural expression among Cretan men.

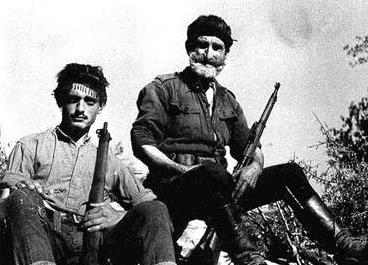

When the Nazis occupied Crete during World War II, they encountered an unmatched resistance. Many Cretan fighters of that time also wore the sariki; the same symbol of pride, resistance, and mourning first worn by the 300 warriors who defied an empire.