Until recently, it was believed that beer was discovered in Egypt around 5,000 years ago and spread to other regions from there. However, increasing research over the past decade suggests that origins of beer was an innovation of pre-agricultural hunter-gatherer societies, dating back 12,000 to 13,000 years. Advances in archaeology show that beer is humanity’s oldest beverage, and Anatolia played a key role in the cultivation of malt and the development of beer production.

Beer is one of the most significant indicators of human interaction with nature and plants. In the past, during abrupt climatic changes, beer’s nutritional value contributed to the survival of communities. Moreover, the need to supply and store this nutrient throughout the year led to grain production and, consequently, the birth of agriculture. With a history spanning over ten millennia, beer may be the oldest beverage of this land; Anatolia’s own product and one of the most significant innovations in its past.

Modern archaeological analyses now provide more detailed insights into the distant past. Archaeologists generally agree that beer; a beverage made from cereal grains or other starchy plants; was consumed even before the advent of agriculture. This suggests that beer may have played a motivating role in the domestication of plants. In fact, many experts believe that beer became part of rituals and competitive feasts even before the rise of sedentary life.

These findings go beyond beer’s discovery, offering a deeper understanding of these communities’ lifestyles. Beer not only triggered the development of agriculture; the foundation of modern life; but also became a central product in organizing settled life and human relationships. Ethnographic examples, as well as archaeological data, indicate that beer was closely associated with feasts, ceremonies, and offerings.

How Did Humans Discover Beer?

A few millennia before sedentary life began in Southwest Asia, Epipaleolithic hunter-gatherers discovered, and even mastered the beer-making process. These communities gradually approached beer production through the collective harvesting of cereal grains and their processing technologies. Tools developed by Epipaleolithic communities, such as sickles, baskets, storage units, mortars, grinding stones, and boiling stones, accelerated their encounter with beer.

Toward the end of the last Ice Age, hunter-gatherer groups surviving in caves of Southwest Asia began interacting more intensively with wild plant species around them, altering their dietary habits fundamentally. These groups developed tools for collecting plants that met their nutritional needs, healed their ailments, or provided pleasant flavors and aromas. They crafted small mortars and stone containers to dehusk and crush wild cereal grains. As human interaction with plants intensified, these tools evolved rapidly. These communities didn’t just consume hunted animals; they softened various plant seeds and grains by crushing them in mortars and mixing them with water into a porridge-like consistency for consumption.

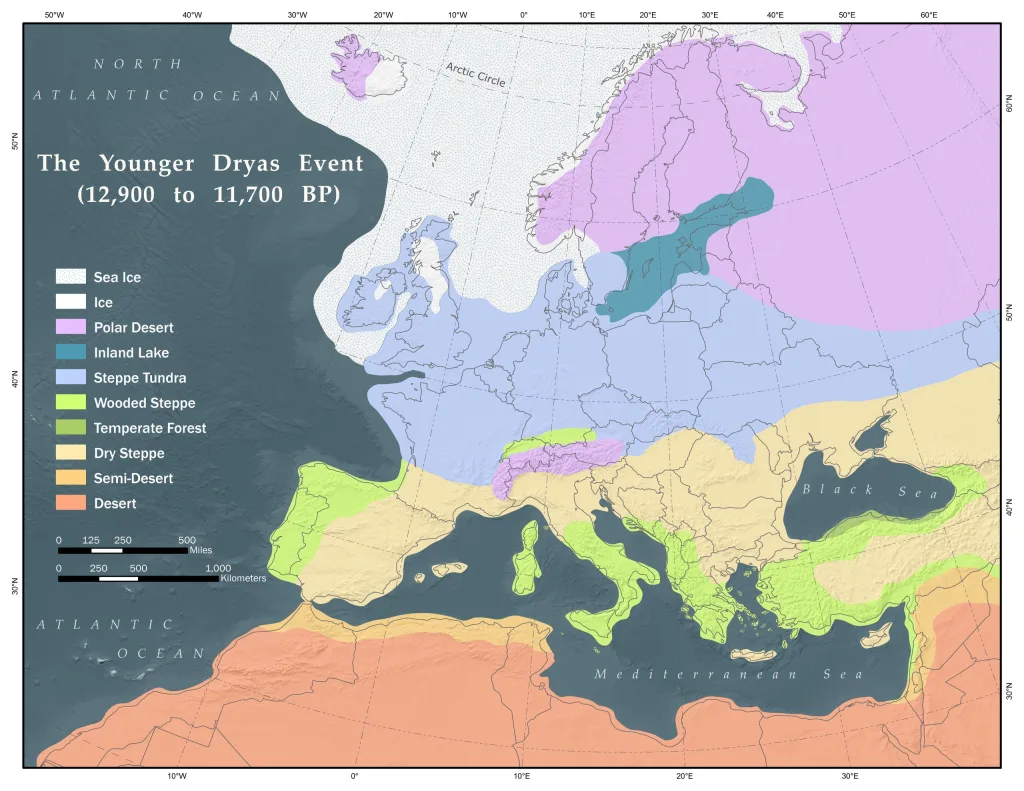

During the Younger Dryas (c. 12,900–11,700 years ago), a sudden climatic crisis forced hunter-gatherers to become less mobile to survive harsh conditions. This new reality required them to settle in more optimal locations year-round. Archaeologists suggest that beer’s nutritional value likely contributed to these communities’ resilience in challenging climates.

They now had to plan for the long term, requiring the acquisition and storage of grain for prolonged consumption. Deep mortars weighing over 100 kg, used to process wild grains, are indicators of this shift. Why did these people carve such massive stones into deep mortars through painstaking processes? Likely, these mortars were prestigious display objects. The social dynamics producing such objects suggest that inter-community feasts were becoming increasingly competitive displays. Beer was now being prepared in these monumental mortars. Sustaining production at this scale would have required larger grain storage. For a community of over 100 people, securing continuous food supplies and mitigating risks would necessitate planning for increased grain production. While not the sole factor, considering its nutritional value, beer likely played a key role in this process.

Anatolia’s Oldest Beverage

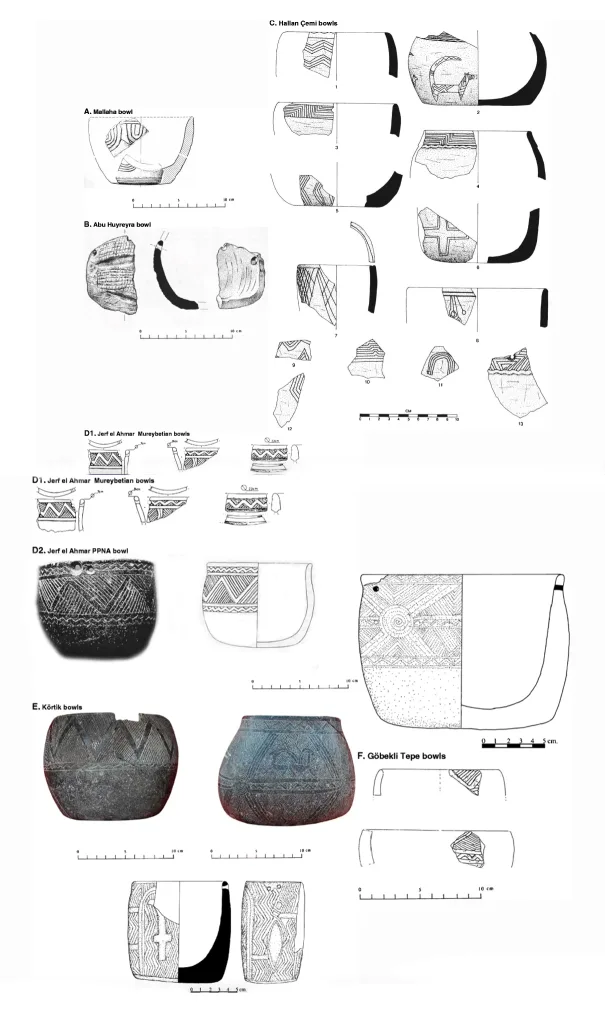

The elaborate chlorite stone vessels and bowls crafted by the first settled communities, decorated with motifs of wild animals, likely point to activities like liquid transport and beer consumption. Beyond daily use, these extraordinary prestige vessels; thought to serve feasts and offerings; have been found across settlements from Northern Syria’s Middle Euphrates Region to Batman and Şanlıurfa, including Göbeklitepe, spanning hundreds of kilometers. As different communities traversed long distances to meet periodically, they probably presented beer in these impressive stone vessels to impress others.

Did these gleaming chlorite stone vessels proliferate as representations of beer-centered feasts? Most likely, yes. Thus, beer influenced not only the emergence of agriculture but also human relationships and the material culture mediating those relationships; much like today’s varied beer bottles and glasses. Beer’s social bonding power, combined with its taste, aroma, and nutritional value, explains why humans have continued consuming it without interruption. We can also consider that the feasts where beer was consumed facilitated cultural convergence among different hunter-gatherer groups, accelerating harvest activities.

Such feasts gradually began to take place in more carefully constructed, solid, and impressive communal buildings. In other words, beer-related activities may have influenced the emergence of shared/public spaces. Perhaps the first “October Fests” began in Anatolia, in these extraordinary places where different communities gathered. These events, uniting human groups around shared cultural activities rather than resource conflicts, created a geography devoid of violence.

Undoubtedly, at least 12,000 years ago, the distinct smells and appearances resulting from the fermentation of grain and water caught someone’s attention, and this curiosity influenced many radical changes, including the advent of agriculture.

Beer Was Domesticated in Anatolia

Plant DNA evidence shows that einkorn wheat was domesticated in the same region as Göbeklitepe and Nevali Çori, while barley spread later from Jordan and Syria to northern areas like Anatolia. For a long time, the earliest beer-drinking communities consumed a type of beer made from either wild barley, domesticated einkorn wheat, or a mixture of both. For example, analysis at Göbeklitepe revealed Triticum monococcum (einkorn wheat), Hordeum spontaneum (wild barley), and Hordeum vulgare (wild barley) within a stone vessel. While this data alone is insufficient, use-wear analysis indicates both fine and coarse processing of grains at Göbeklitepe. Starch analysis showed no preserved starch;likely due to heat exposure during subsequent uses of the stone vessels, which destroyed surface starch. Nonetheless, another biochemical analysis detected oxygen- and nitrogen-containing residues inside the vessel.

Barley Harvest Dates Back at Least 19,000 Years

Barley (Hordeum vulgare) is one of the world’s earliest and perhaps most important domesticated cereals. DNA studies show that barley was domesticated in at least five different regions in a mosaic pattern. Barley didn’t spread from a single location but was domesticated across a broad geography, including Anatolia, the northern and southern Levant, Syria, and the Tibetan Plateau. However, initial harvesting activities, domestication, and transformation into a form of agricultural economy took place in Southwest Asia, including Anatolia. About 10,500 years ago, people cultivated barley, but even 19,000 years ago, they harvested wild barley, dehusked it, ground it, and consumed it.

This resilient cereal, sprouting in winter, is not endemic to Mesopotamia alone; it is found from China to Europe, across much of Asia and Europe. Barley can grow in marginal areas, at varying altitudes and climates. Wild barley is usually covered with a husk and has two rows of kernels. The husk protects the kernels like a shell. The huskless variant; called naked or hulless barley; signals domestication, as two-row kernels give way to six-row ones. Even though domesticated barley produces more kernels, husked varieties persist. Humanity cultivates both husked and huskless barley, in two-row and six-row forms.

It appears that beer is not just humanity’s oldest beverage but also a special drink that unites and bonds people. Thus, beer stands at the center of a kind of competition, with its aroma, color, and flavor. Archaeological records indicate that past communities eventually localized beer production by brewing beers of varying bitterness, color, strength, and flavor. Brewing slowly became a significant craft, where recipes were passed down generations, and yeast cultures; key to production; were carefully maintained.

Today, we owe the standardized yeasts that give beer its flavor, aroma, and durability to Louis Pasteur, who understood their structure and how to control them. Yet, it wouldn’t be wrong to say that the traditional beer-making practices; produced through natural processes and sensitive to every environmental change; spread from the ancient world, including Anatolia.

From Stone Vessels to Clay Pots

Human interaction with yeast diversified rapidly with the onset of settled life. People needed new spatial arrangements to store more products year-round, especially enough to survive harsh winters. The rise in birth rates within settled life changed household structures under the same roof. Managing the growing population became a more pressing issue to sustain settled communities. Expanding agriculture and tending to domestic animals like sheep, goats, and cattle meant increasing workloads and responsibilities. Processes like sowing and harvesting became activities requiring division of labor and social organization. The food obtained from cultivated plants was essential for the community’s survival and continuity of settled life. Not just production mechanisms but also sharing and consumption dynamics became central challenges of life, bringing social competition and stress. Communities used shared spaces, rituals, and feasts rooted in their hunter-gatherer ancestors to maintain unity and reduce stress. Beer remained a key element of these celebrations.

With the domestication and widespread use of barley by early settled communities such as those in volcanic Cappadocia’s Aşıklı Höyük and Konya’s Çatalhöyük, a new era began for the history of beer in Anatolia. From the 8th millennium BCE, as plants, fruits, and nuts gained prominence in new dietary habits, bread and porridge made from different varieties of wheat and barley marked the beginnings of culinary culture. These communities, consuming higher-calorie diets than their hunter-gatherer ancestors, began to view beer; resulting from the chemical transformation or fermentation of grains;not merely as a nutritious drink but as a beverage that aided digestion.

In the 7th millennium BCE, the invention and spread of pottery in Anatolia radically changed human interaction with fermented foods and beverages. Neolithic communities soon began making heat-resistant pots. Beer reemerged: it found vessels and containers to ferment, store, mass-produce, and even trade.

Large-Scale, Specialized Production and Storage

Clear evidence of beer becoming part of daily life and trade first appears in Anatolia during the Early Bronze Age, about 5,000 years ago. A pottery shard from İmamoğlu Mound, now submerged beneath Keban Dam in modern Malatya, depicts two people drinking together using long straws from a central vessel. Could this liquid be beer?

At Kuşaklı, a Hittite settlement excavated in Sivas, two-row barley (Hordeum v. distichon) was the dominant cereal. Barley grains found in the beer workshop were much larger than those elsewhere in the settlement, suggesting that special barley was selected for beer production. Data from this 3,200-year-old brewery reveal that madımak (Polygonum cognatum) was added to the beer as a sweetener. This practice predates the widespread use of hops in Europe by many centuries. While madımak imparted a sour taste, its high oxalic acid content also extended the beer’s shelf life. As one of the key plants in Hittite cuisine, madımak contributed not only to fermentation but also offered antimicrobial and antioxidant properties.

At Boğazköy-Hattuşa, the Hittite capital, a site believed to be a brewery yielded large vessels used for grinding and narrow-necked amphorae sealed with clay to prevent bacterial contamination. The presence of emmer wheat at the site suggests the Hittites brewed a pure wheat beer.

Beer Was Drunk with Straws – and Not Alone

Archaeology connects scattered finds into coherent narratives. We know from archaeological parallels that the liquid depicted in İmamoğlu Mound, shared between two people via long straws, was likely beer. A bent straw fragment made of lead, found on the Uluburun shipwreck dating to 3,300 years ago, helps us understand this depiction. The 11 cm-long, 1.5 cm-wide straw fragment, now in Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology, matches beer straw tips commonly used in Egypt. A perforated straw tip, dated to 3,000 years ago, was also found in the brewing room at Kuşaklı in Sivas.

At Kültepe in Kayseri, seals from the Assyrian Trade Colonies period show people drinking from a container using straws. All these examples indicate that beer, which left sediment at the bottom of the vessel, was consumed through filter straws; and always communally.

Neighboring Sumerians also drank beer from communal deep bowls using straws, as depicted on seals and described in the earliest inscriptions. Thus, across a vast region from Anatolia to Mesopotamia, beer was a drink shared, not consumed alone. In this context, it’s fair to say that innovations and competition in brewing, alongside local recipes and flavors, were becoming significant across this wide geography.

Irresistible Flavor: Malt

For the Sumerians, beer was so vital that they had a beer goddess named Ninkasi. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, bread and beer transformed the wild Enkidu into a human. Perhaps the bread mentioned was a bitter bread made from a widely consumed malt. Many cuneiform texts describe the trade of such malt bread between Anatolia and Mesopotamia. Not only the Sumerians but also the Hittites consumed a bitter bread made from malted barley as a daily staple. Malt; made from germinated barley; was also consumed as a pudding-like food in special rituals. Malted barley began to dominate not just in bread and puddings but also in beer production. Malt beer was the centerpiece of over a hundred Hittite festivals.

During the Karahna festival, spanning three days and seven celebrations, people were required to make offerings to the gods. A 3,300-year-old tablet from Boğazköy states: “During the year, they offer them four cattle, 39 sheep, 24 measures of flour, and 25 vessels of beer.” Even Hittite gods drank beer. Every temple had its own brewery, where beer was produced and presented in jugs as offerings to the gods.

In the Thunder Festival, celebrating the Rain and Storm God, a tablet describes placing the harši-vessel under rain in spring and grinding its contents. Both cooked and raw lamb were presented as offerings, alongside thick bread, which was distributed into rhyton vessels. After this meal, one vessel of beer was dedicated as an offering, and three vessels were set aside for display. Then, everyone recited together: “Oh Storm God, let the rain increase abundance, and let the dark earth be satisfied! And Storm God, let thick bread be plentiful!” Finally, a huppar-vessel of beer was poured onto the ground as a libation.

Thanks to modern archaeology, we now understand that beer is humanity’s oldest beverage and that Anatolia hosted the production and development of malt and beer. Beer was not only a marker of human interaction with plants and nature but also played a central role in strengthening communal memory and social unity through celebrations and rituals. With its diverse recipes, distinct flavors, and a history stretching back over 10,000 years, beer is the oldest and most natural drink of these lands; Anatolia’s own product. Perhaps most importantly, beer was a key motivator behind the emergence and spread of agriculture. In light of this knowledge, it would not be wrong to say that beer is one of Anatolia’s first intangible cultural heritages.