The concept of time is both directly relevant to human life and broad enough to evade universal definitions. Our perception of time relates to the dimensions we interact with, leading to the emergence of multiple and differing understandings of time. While there are numerous and diverse narratives about such a vast concept, for Muslims, the foundation of their understanding of time is undoubtedly shaped by the Qur’an and the Sunnah. Let’s discover Saatnâme, which are manuals of Islamic timekeeping.

God’s swearing by “time” in the Qur’an emphasizes its immense value, while other references to time in the text provide knowledge that exceeds human experience. This concept, sometimes presented in absolute terms and sometimes relatively, led to the formation of a specific literature within Islamic history. Interest in time’s relationship with existence and its divinely emphasized significance fostered the emergence of religiously anchored literary genres that approached the subject from various angles. Works such as Melhame, Ruzname, Ilm al-Nujum, Sâ‘at-i Zamaniyye, Yıldızname, Şemsiyye, Sab’a-i Seyyare, Zayiçename, and Saatnâme are notable examples. Alongside these works, disciplines like astronomy -developed further by Muslims due to its relevance to worship schedules- served as essential sources.

Astrology and Timekeeping in the Islamic World

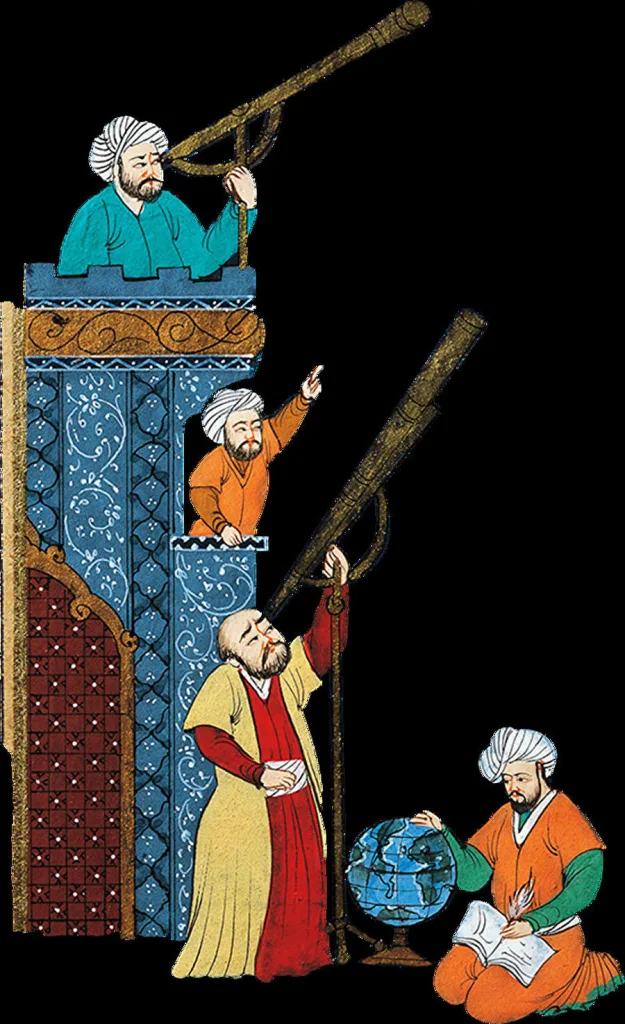

Astrology (Ilm al-Ahkâm al-Nujum), which appeared somewhat later than astronomy, received considerable attention in Islamic civilization, comparable to that in other cultures, and was employed to predict the past, present, and future. For instance, in the Ottoman Empire, müneccims (court astrologers) were responsible not only for preparing calendars and timetables (imsakiye) but also for determining auspicious and inauspicious times (zayiçe). The phrase “eşref saati” (auspicious hour), still used today, held critical importance in Ottoman life. The earliest known record concerning eşref saati dates back to the reign of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror. In his Fetihnâme of Istanbul, Tacizade Cafer Çelebi noted that Sultan Mehmed launched his final and decisive assault during the auspicious hour indicated by his astrologers. Ottoman sultans often consulted müneccims to determine the eşref saati before embarking on military campaigns or organizing state affairs in line with astrologers’ recommendations.

The Origins of Saatnâme Literature

One of the key influences behind the emergence of the saatnâme genre within this broader literature was the Qur’anic emphasis on the superiority of certain times over others—such as the declaration that the Night of Qadr is better than a thousand months. Such verses inspired efforts to understand the value of time and observe auspicious moments. The term saatnâme combines the Arabic word sâ‘at (meaning “time” or “clock”) with the Persian suffix -name (meaning “book”), thus denoting a treatise about time or timekeeping. Drawing from Ilm al-Nujum (astronomy/astrology), saatnâmes are didactic texts -written in prose or verse- that explain how to determine specific times and their spiritual significance or effects.

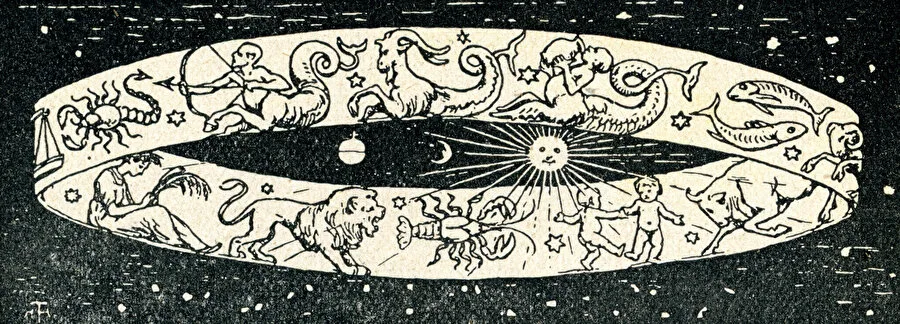

Relying on calculations rooted in Ilm al-Nujum, saatnâmes detail activities that should or should not be performed at specific times, based on the seven planets and twelve zodiac signs (Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces). A single day is divided into seven distinct periods: tulû, kuşluk, zevâl, öğle, beyne’s-salât, asr, and ahir-i rûz (though naming and classification vary by author). Each of these periods is analyzed in relation to the influence of Venus (Zühre), Mercury (Utarit), Sun (Şems), Moon (Kamer), Saturn (Zühal), Jupiter (Müşteri), and Mars (Merih). Guidance is provided on which activities are appropriate for specific times or days, based on the condition and influence of these celestial bodies.

Content and Purpose of Saatnâmes

Among the topics addressed in saatnâmes are acts of worship deemed suitable for particular times, recommended prayers, eschatological discussions, general religious knowledge, and moral advice. Even mundane matters -like personality traits based on birth time, wearing new clothes, setting out on journeys, hunting, engaging in commerce, or bloodletting- are discussed in relation to timekeeping. Alongside the spiritual dimensions of time, saatnâmes also touch upon cosmic phenomena, including seasons, rainfall, snowfall, and other natural events. While rooted in Ilm al-Nujum and religious texts, these works often incorporate israiliyat (Judeo-Christian traditions) and folk mythology.

The earliest known author of a saatnâme is Hibetullah b. Ibrahim, whose exact date of death is unknown. In his work, he identifies his sources as follows: “This book, known as the Saatnâme, was compiled and translated from many noble books, supported by the evidence of the Qur’an and the Prophetic Hadith.”

Though similar in some respects to other treatises written about the days of the week, saatnâmes tend to offer more comprehensive guidance, covering empirical observations, meteorological phenomena, and diverse topics. For example, a saatnâme might advise: “Each day has an auspicious hour. Today begins nobly, but a robe tailored today will bring its wearer misery and sorrow. Those shaved today will not find relief from grief until this day recurs.” Similarly, one text describes Monday as follows: “Do not journey eastward. If today is the first of Muharram, winter will be harsh, summer hot, honey and inheritance plentiful, yet weeds will suffer, women will die in Khorasan, there will be prosperity in Kuhistan, but famine in Pars.” Another text concerning December (Kânûn-ı Evvel) states: “If a solar eclipse occurs, rain and snow will be abundant, winter severe, grain and grass plentiful, fish and other birds abundant, while conflict will erupt in the Maghreb and many nobles will perish in Arabia.”

History and Prominent Works of Saatnâme

Although it is unknown who authored the first saatnâme or when it was composed, the genre is believed to have emerged between the 8th and 9th centuries CE. A saatnâme manuscript dated 1670 notes that it was translated from a work by Abū Ma‘shar al-Balkhī (d. 886). This suggests that the tradition of saatnâme writing may have begun with him. Although no work explicitly titled Saatnâme by Abū Ma‘shar al-Balkhī survives, his astronomical texts likely provided foundational material for later saatnâme literature. Some saatnâmes were standalone works, while others appeared as chapters within larger compilations: such as Erzurumlu İbrahim Hakkı’s Marifetname.

The most renowned saatnâme is attributed to Hibetullah b. Ibrahim, whose work survives in the largest number of manuscripts in Arabic and Persian, preserved in manuscript libraries. Other notable contributors to the genre include Abū Ma‘shar al-Balkhī, Abdülganî bin Celîl Geredevi (d. 1586), and Erzurumlu İbrahim Hakkı (d. 1780).

The Cultural Legacy of Saatnâmes

Emerging from Muslims’ desire to align both their acts of worship and daily activities with auspicious times, the saatnâme genre offers valuable insights into Islamic concepts of time and its social, religious, and cosmic dimensions. Today, these works represent a rich cultural heritage deserving study in the fields of history, religion, literature, and science. Hibetullah b. Ibrahim explicitly wrote his treatise as a form of spiritual guidance, assuring readers that those who follow its advice -rooted in religious teachings- will earn divine rewards in the afterlife and benefit from his intercession on the Day of Judgment.