Today, wine, coffee, or chocolate tasting events are quite familiar to us. But what about water? And not just to quench thirst:imagine water that is carefully selected like a fine wine, proudly listed on a menu, and even replacing champagne in wedding toasts… It may sound surprising, but such waters promise far more than ordinary mineral or tap water, and their prices can reach hundreds of dollars per bottle. In modern terms, “water sommeliers” pair different waters with dishes from fish to steak, desserts to cheese plates.

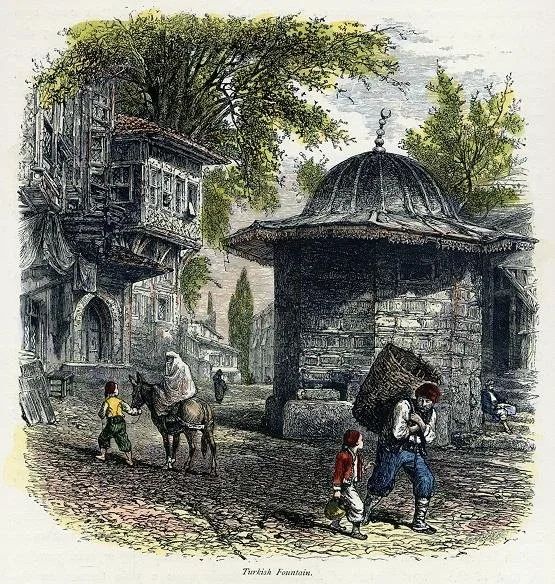

19th-century Ottoman fountain engraving – Around today’s Üsküdar

Although luxury water consumption seems like a modern trend, this practice has deep roots in the Ottoman Empire. The spring waters of Istanbul were so highly valued that recognizing and evaluating them was considered an art.

The Refined Science of Water in the Ottoman Empire

“Saka” (Ottoman water carrier)

In the early 19th century, Prussian officer Helmuth von Moltke, invited to Istanbul by Sultan Mahmud I, spoke with admiration about the city’s water culture:

“When a Turk tastes a sip of water, he can tell from which favored spring it comes. From Çamlıca, Bulgurlu, the Chestnut Spring near Büyükdere, or the Sultan Spring in Beykoz… Just as our wine experts can identify the vineyard and vintage, they can tell the source of the water.” (Moltke, 1836)

Behind this skill lay both a refined palate and intimate knowledge of the city’s water network. In Ottoman Istanbul, water was not merely a necessity: it was a symbol of social status and elegance.

The City’s Spring Treasures

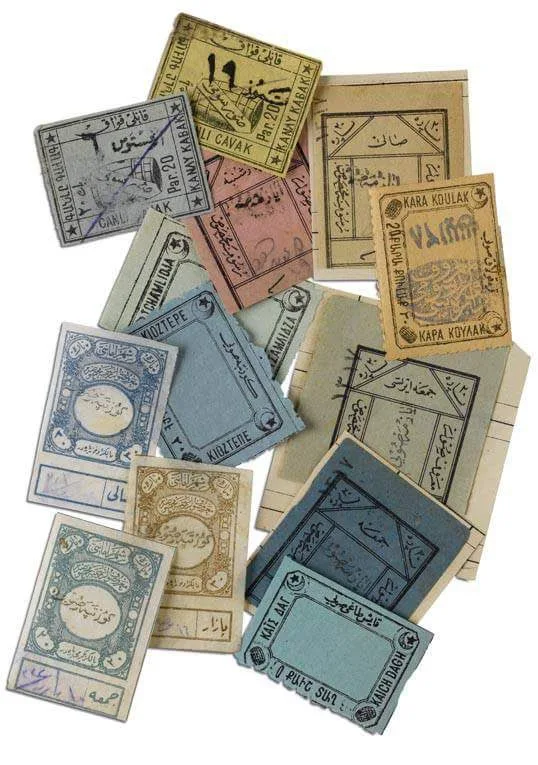

Stamps prepared for spring waters

In the Ottoman era, Istanbul’s water sources were distributed through dams, reservoirs, and fountains. Yet not all waters were considered equal:

- Great Çamlıca Water: Believed to aid digestion, its sale was prohibited by order of the Council of State, reserved exclusively for public use. In his novel İntibah, Namık Kemal praised it as “âb-ı hayat” (the water of eternal life).

- Karakulak Water: Discovered in the 1700s, this spring became a life-saver during the 1892–95 cholera epidemic. It was specially distributed to Mekteb-i Mülkiye students and soldiers. Every week, water from Beykoz was shipped to Paris for Namık Kemal and Ziya Pasha.

- Sultan Spring & Chestnut Spring: Located on opposite shores of the Bosphorus, famous for their refreshing taste and “lightness.”

Water Drinking as a Cultural Ritual

Abdullah Frères photo: water-carrying person

Water tasting was not merely technical evaluation: it was a ritual. Author Engü Ertel recalls how his father would take out a leather-cased crystal glass to drink Çamlıca water, and how marble fountains had ornate brass spouts covered with gauze for cleanliness.

In Five Cities, Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar remembers Istanbul first through sound. To him, it was the voice of an old woman murmuring the names of springs: “Çırçır, Karakulak, Healing Water, Hünkâr Water, Taşdelen, Sırmakeş…” Writer Selim İleri likens her to a “spring fairy,” imagining her as a guide through the city.

A Taste That Lingers from Past to Present

One of contemporary practitioners: Alican Akdemir

Today, water tasting is a professional discipline that examines how minerals, hardness, and temperature affect the palate. Yet the Ottoman water culture encompassed far more; it was a reflection of the city’s spirit and identity.

Perhaps one day, as you sip a glass of Çamlıca water, you will agree with the water tasters of centuries past. For some flavors linger not only on the palate but also in history itself.