Nail Çakırhan was born in 1910 in the Ula district of Muğla, Turkey. His father traced their lineage back twelve generations through gravestones and discovered that their roots extended to Arabia. Çakırhan believed that his ancestors may have descended from Janissaries who passed through Ula during Suleiman the Magnificent’s 1522 Rhodes campaign and decided to settle in the area.

When his parents got married in 1907, his grandfather Hacı Hasan built them a two-story house, and that is where Çakırhan was born.He describes his childhood in Ula as follows:

“Ula, with a population of three thousand, was a beautiful place…”

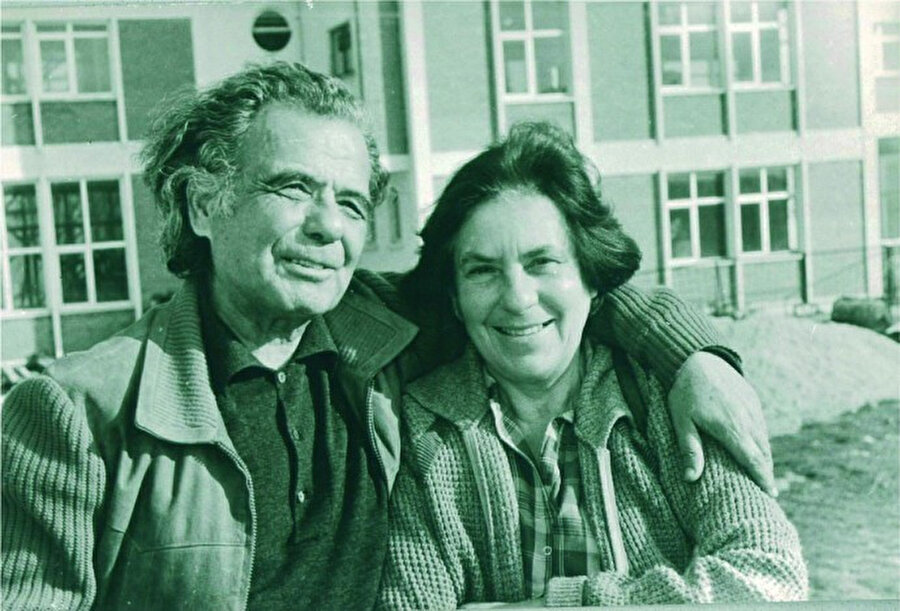

Nail and Halet Çakırhan

From Religious Education to Revolutionary Ideas

Çakırhan began his education at home and was so successful in religious studies that his teachers advised his family to send him to Al-Azhar Mosque in Egypt. However, under the influence of his uncle, he drifted away from the religious path. He continued his secondary education as a boarding student in Muğla. Thanks to his mother selling her gold, he then attended high school in Konya, becoming the first child from Ula to attend high school.

Kartepe Project

First Steps into Literature and Controversy

In high school, he published three literary magazines: Müntehebat, Halka Doğru, and Kervan. In his first poem published in Kervan, he was taken to court on charges of “insulting women” but was acquitted. In another poem, he was accused of calling Atatürk a dictator but was saved by Atatürk’s personal order.

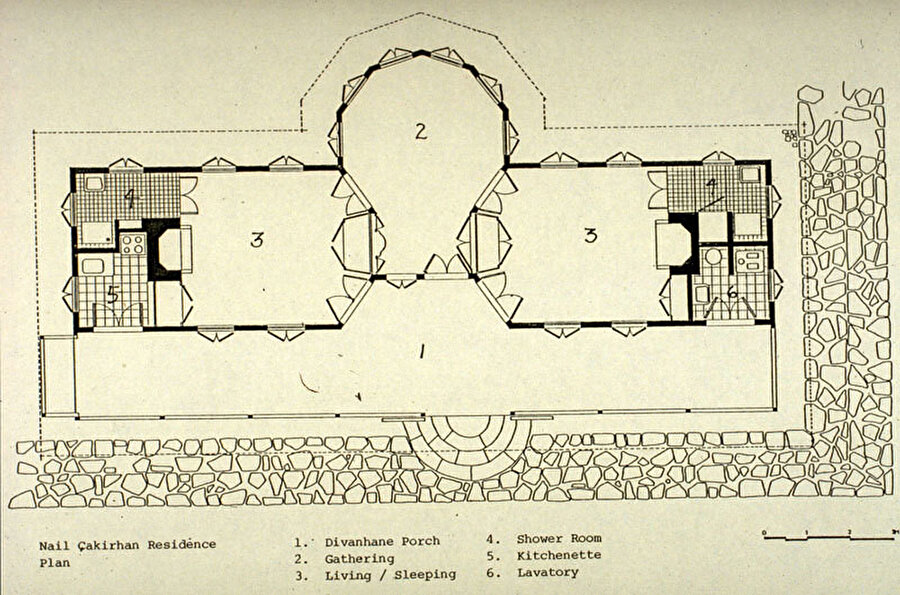

Sketch of Çakırhan House

Istanbul Years: Influences of Nazım Hikmet and Political Awakening

In Istanbul, he formed friendships with figures like Tanpınar and Peyami Safa, and became close with Nazım Hikmet and Sabahattin Ali. He joined medical school under family pressure but left it with Hikmet’s encouragement, joining the Communist Party and working for Resimli Ay magazine. He was imprisoned alongside Hikmet and others. After 17 months in prison, he turned to publishing and later traveled to Moscow. He lived as a Soviet citizen, worked in factories, visited Lenin’s mausoleum, married a Russian woman, and experienced communism firsthand.

Çakırhan House

Return to Turkey: From Political Activism to Bookstores

Back in Turkey, he served in the military and opened a bookstore. He socialized with intellectuals such as Mina Urgan, Necip Fazıl, and Abidin Dino. He later married archaeologist Halet Çambel. Nail Çakırhan engaged in publishing and co-founded the Socialist Workers and Peasants Party in 1946, which was later banned. He was imprisoned again, reunited with Çambel in Paris, and returned to Turkey.

Entering Architecture by Necessity, Not Title

In 1957, during Çambel’s excavation in Kartepe, no contractor would build Turgut Cansever’s canopy design. Çakırhan took the job and thus began his accidental architecture career, introducing exposed concrete and establishing literacy courses for locals. The project’s success led him to construct the Turkish Historical Society building. German officials later offered him school construction jobs, which he completed successfully, earning significant income.

Çakırhan House

Building a Philosophy in Akyaka: Simplicity and Craft

In 1968, advised to rest by the sea, he returned to Akyaka. He built a traditional single-story wooden house with the help of aging craftsmen. Initially mocked, his home became the model for future architecture in the area.

“I’m not an architect… but at that time…”

He built 18 houses between 1970 and 1983, all rooted in traditional methods and minimalist lifestyle.

Recognition and Rejection: The Aga Khan Award Controversy

In 1983, he was selected for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. He won with his own house in Akyaka, but Turkish architects reacted negatively. Accusations of communism reached Kenan Evren, but the award proceeded. He received the award at Topkapı Palace and used the prize money to reward workers and restore Muğla’s Cultural Center. His influence shaped local architecture in Akyaka.

Turkish Historical Society

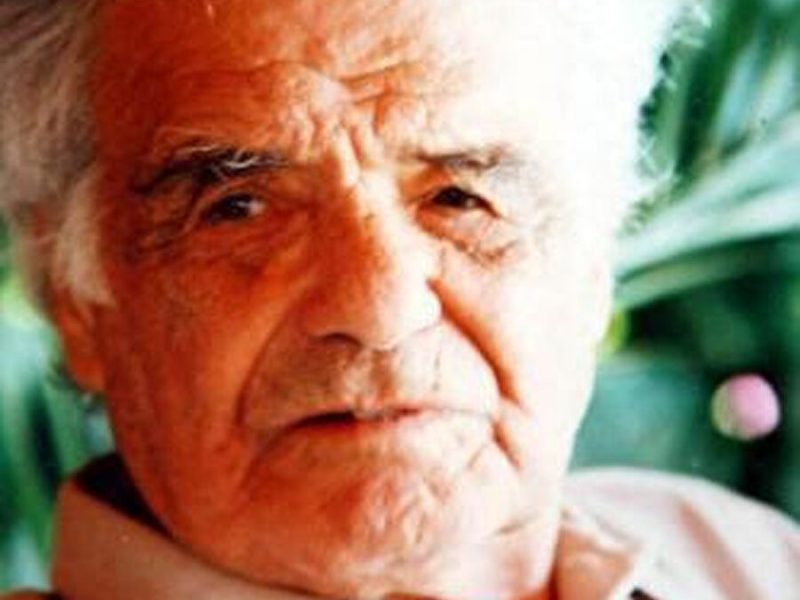

Legacy of a Man Beyond Titles

He never charged for the houses he built and lived modestly. He and Çambel avoided luxury and lived simply. His architectural approach was echoed in local government policies.

The Architect Who Wasn’t: What Nail Çakırhan Teaches Us Today

One of his final works was a holiday village in Fethiye, built without cutting a single tree. His approach respected nature and tradition.

When you look at the life of Nail Çakırhan you realize that whatever one does, it must be done with care. Ideologies, education, and actions only gain value when rooted in strong personal conviction.

Çakırhan’s story shows how architecture, life philosophy, and social values can merge beautifully, even without formal training. His legacy gives us clues to what kind of architecture and architects this country truly needs.

“Perhaps, as I sometimes think, he succeeded precisely because he wasn’t an architect.”