Ankara and its surrounding areas have been continuously inhabited since prehistoric times. The known history of Ankara stretches back to the Paleolithic Age. With a history spanning approximately 5,000 years, urban life in Ankara is believed to have continued uninterrupted. Its significance, which began due to its position on the ancient Royal Road, continues today as the capital of modern Turkey.

The earliest settlement within the city center is believed to be the area where Ankara Castle stands today. Over the centuries, the city came under the control of various civilizations, including the Hittites, Phrygians, Cimmerians, Lydians, Persians, Macedonians, Galatians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Seljuks, and Ottomans.

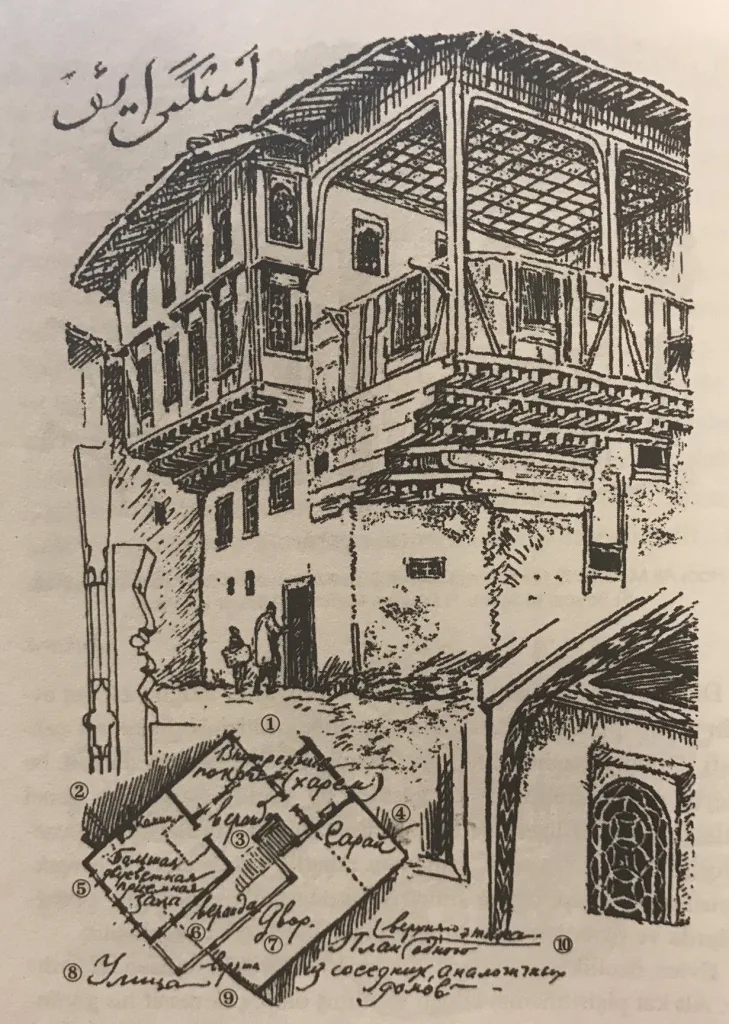

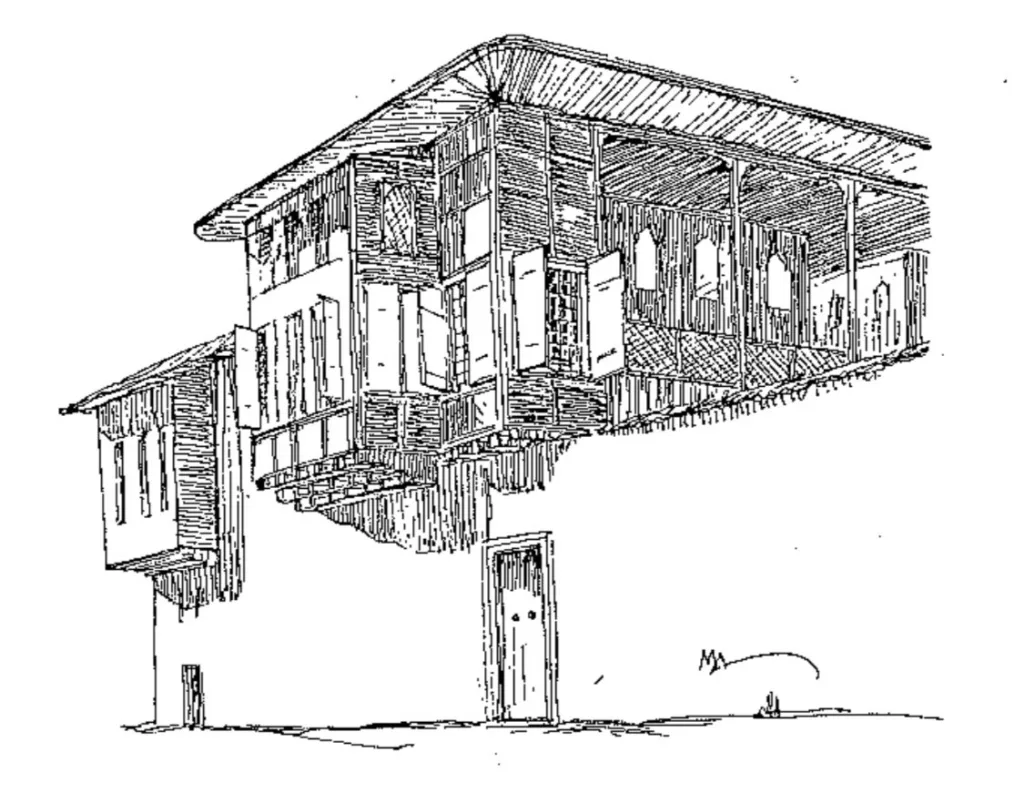

The balcony of a historical Ankara house is described by a beautiful word from our local architectural vocabulary: “Seyregâh.” In Ankara houses, this semi-open space located in a corner of the house, open on the sides but covered on top and supported by wooden columns, was called a “Seyregâh.”

During the Roman period, Ankara reached a population of 100,000, marking its golden age with monumental structures across the city. From the 7th century onwards, it lost its open-city identity, was surrounded by walls, and served as a frontier city. Detailed information about Ankara is scarce until the 16th century, when accounts from travelers and registry books provide insights. Notably, in the 13th century, Ankara was governed like a city-state by the Ahis, during which commerce flourished. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Ankara became an important industrial and commercial center, particularly known for its livestock and leather industries. The city monopolized the production of “sof” and “şali” fabrics woven from the hair of the Angora goat. With a population of 25,000, Ankara was densely populated for its time due to its vibrant industry and trade.

The Seyregâhs, the balconies of historical Ankara houses, are positioned facing the front courtyard of the house, offering a clear view towards the east and partially towards the south. The Russian painter Lansere also depicted the same Ankara house in 1922, together with Harbi Hotan Hoca.

Development of Traditional Ankara Houses

Although religious architecture from the Seljuk period still exists in Ankara, examples of the city’s old houses, which hold a special place in Turkish civil architecture, are rare. The oldest surviving houses are no more than 250 years old, due to their construction from perishable materials like wood and adobe. The shift to settled life and house-building among the Turks began in the 14th century, after the Oghuz Turks established the Ottoman Beylik.

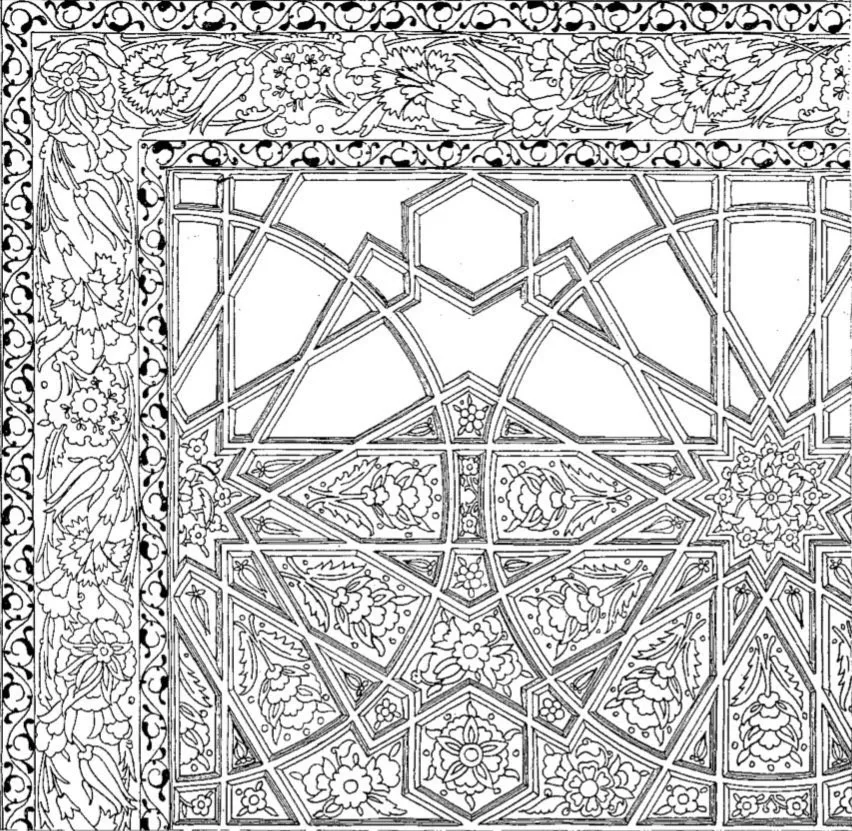

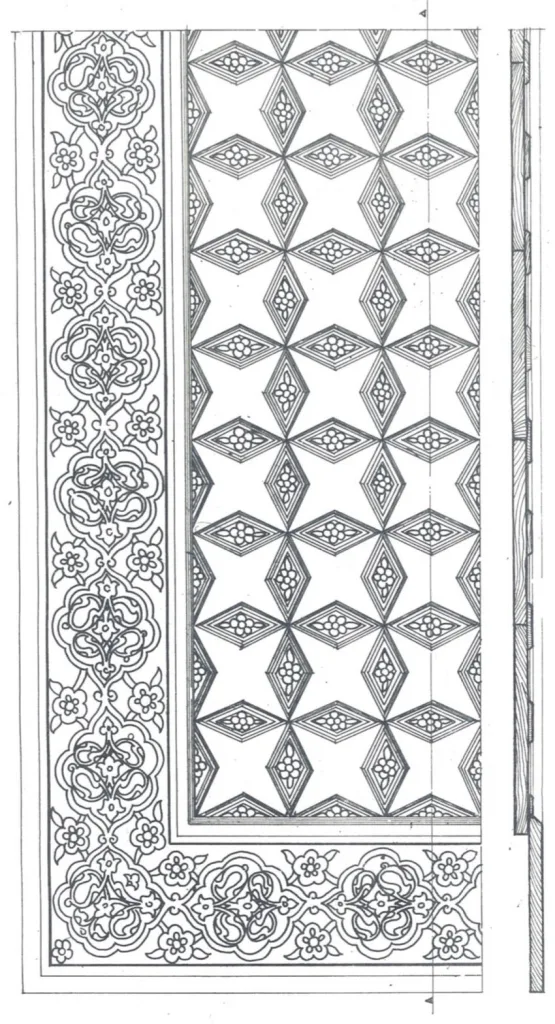

The Seyregâh (balcony) and ceiling decoration of the Nazım Çerkeş House in Ankara. If the Seyregâh faces the courtyard or garden, rather than the street, it can be considered similar to the architectural element known as “hayat.”

The oldest recorded house in Ankara is the Kadınkızzade Abdülhalim Efendi Mansion, built in 1702 in the Mururi neighborhood near Samanpazarı.

Today, there are unfortunately no fully preserved houses reflecting the original architecture. The existing Ankara houses, mostly around 150 years old, have lost much of their authenticity due to various alterations.

The Celali Rebellions of the 16th century devastated areas like Samanpazarı, Karacabey, and Hamamönü, destroying nearly two-thirds of the city. Old Ankara can be geographically defined as bounded by Ahi Yakup to the north, Cenabi Ahmet Paşa Mosque to the east, Hacettepe to the south, and Hacı Doğan neighborhood to the west, including Kaleiçi, Samanpazarı, and Atpazarı.

The Seyregâh and its ceiling… From the book “Old Ankara Houses”, published in 1946 by Mahmut Akok and Ahmet Gökoğlu through the History and Museum Branch of the Ankara People’s House, and printed by the Turkish Historical Society.

Architectural Features of Ankara Houses

Ankara’s streets lacked geometric order, featuring narrow, winding paths no wider than 5-6 meters, sometimes narrowing to as little as 2 meters where even carts could not pass.

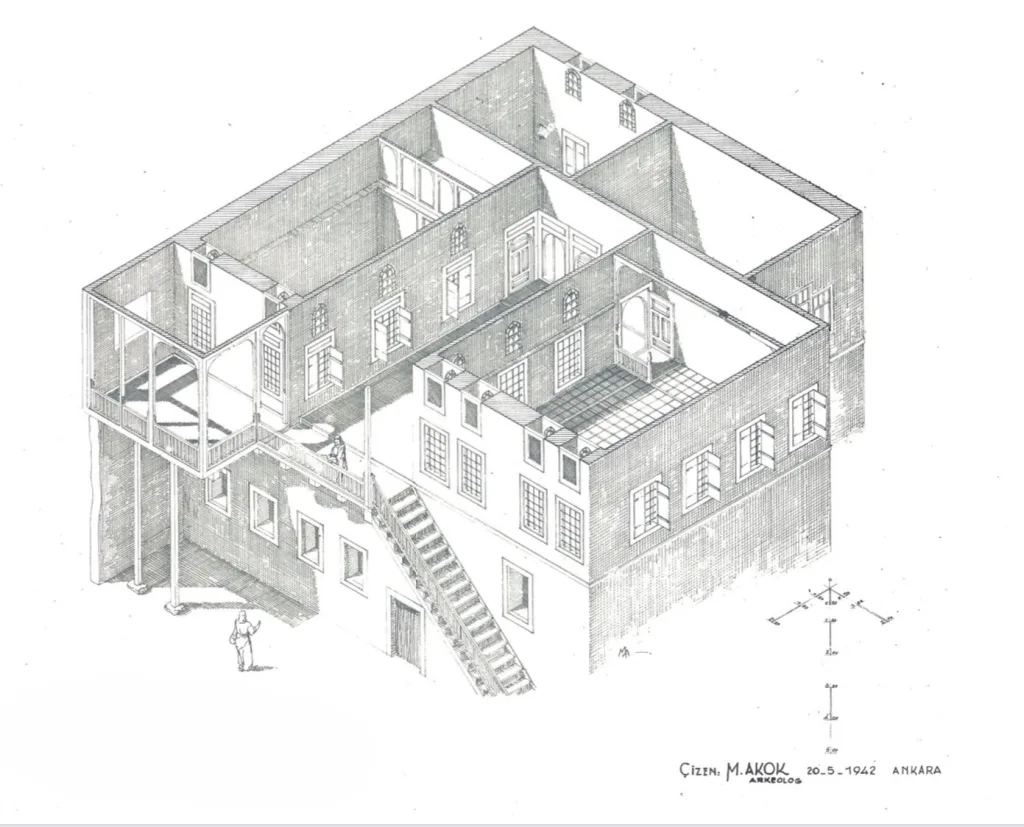

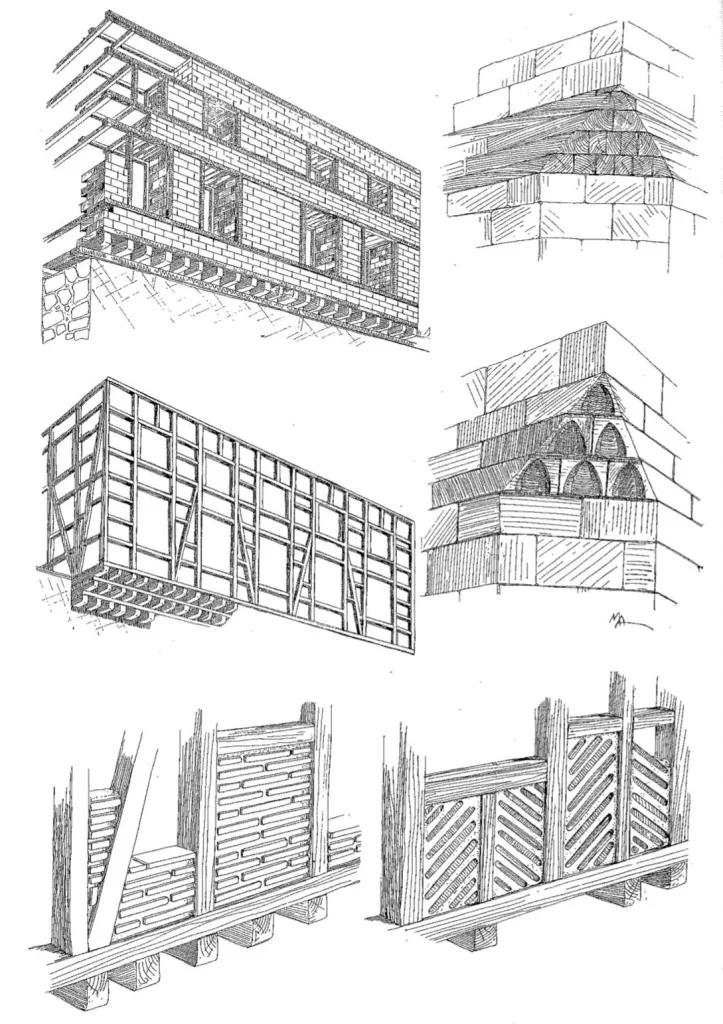

Ankara houses are generally two-story, sometimes three if a mezzanine is present. They are modest, simple, with central halls and oriel windows (cumba). Older houses were single-story, made of adobe with flat earth roofs. The floor plan of these houses follows the ancient “Hilani” type found in Anatolia. The stone foundation supports walls of stone masonry, with adobe and wooden reinforcement bands. The upper walls were mostly constructed using a timber frame filled with bricks or adobe. The so-called Ankara stone used in foundations is a lime-rich andesite, a volcanic stone. Lower stone walls were plastered with lime for aesthetics and cleanliness, while adobe construction was eventually replaced with wooden frameworks.

Ankara houses typically had two sections: winter and summer. The winter section was located on the lower floor and/or mezzanine, built with thick stone walls, few doors, and small windows to withstand Ankara’s harsh winters. Rooms had wooden floors and featured fireplaces, bathing areas, and built-in cupboards. Wooden double-winged doors opened directly to the courtyard, which always included a garden. Courtyards, sometimes referred to as “taşlık” (stone yard), were often paved with stone or earth. An important courtyard element was the “dibek taşı” (mortar stone), usually repurposed from column drums or capitals. Courtyard fountains and toilets were located near entrances for proximity to main sewage channels. Garden walls were 2-2.5 meters high, topped with tiled caps.

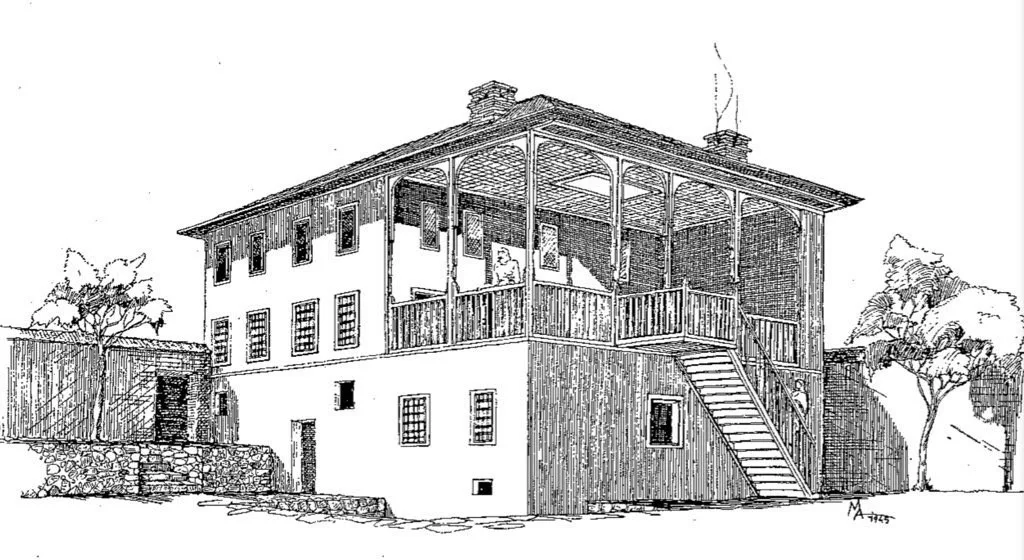

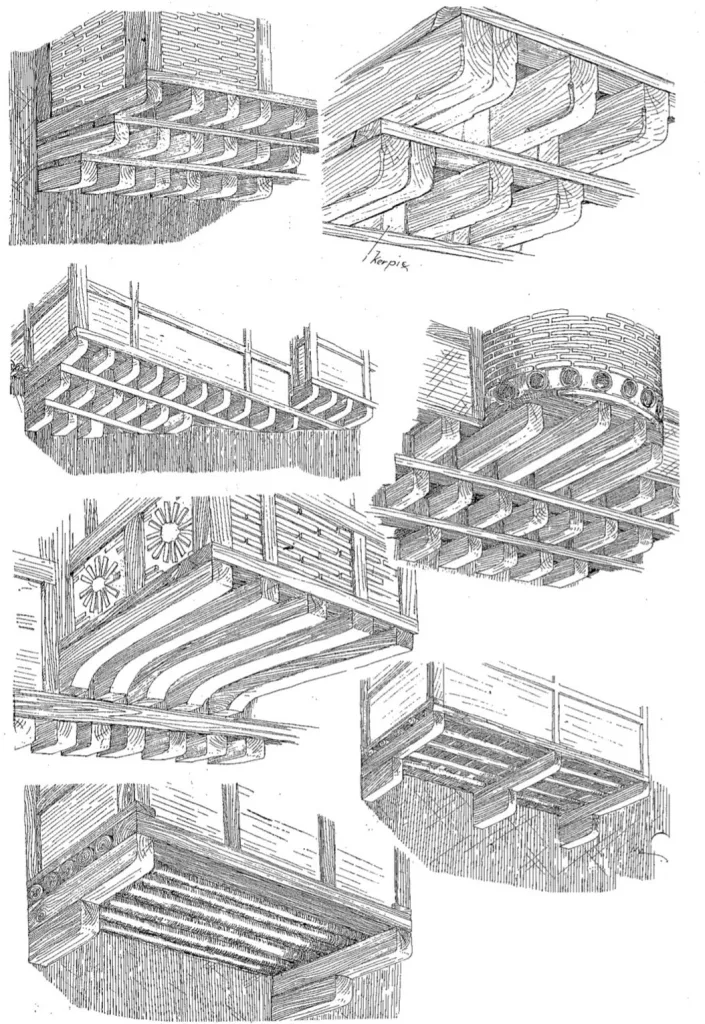

“The Old Houses of Ankara,” 1951. Painter, archaeologist, and illustrator Mahmut Akok published what is perhaps one of the most beautifully illustrated architecture books in Turkey. The projections of Ankara houses, seyregâh details, bevels — all are drawn magnificently.

Cellars were rarely used in Ankara houses. The ground floor housed kitchens, pantries, storage rooms, haylofts, stables, and servants’ quarters.

The upper floors served as summer quarters, accessed by wooden staircases rising from the courtyard, typically beginning with stone steps. A distinctive feature was the “hayat” (life space), an open, wooden-beamed terrace-like area overlooking the courtyard and street, surrounded by wooden railings. The “hayat” was the heart of the house, sometimes containing a scenic corner known as a “köşk” or “tahtseki.” When enclosed, the hayat became a central hall (sofa), or a hallway if surrounded by rooms. Summer rooms featured large windows, thin walls, and included guest rooms (divanhane or kabul odası), bedrooms, and living rooms. The guest room, the largest in the house, had elaborately decorated wooden ceilings with geometric, animal, or plant motifs, plaster fireplaces, cupboards, and low divans lining the walls.

Oriel windows (cumba) were almost universal, often supported without visible brackets (bingi).

One of the characteristic features of Ankara houses was their wide eaves with simple, balanced corners. These eaves protected walls from rain and snow in winter and provided shade in summer. Roofs were wooden and tiled, with tile use becoming common from the 18th century onward, initially among wealthier classes.

The “selamlık,” or men’s quarters for male guests, was the most ornate part of the house, though separate selamlık-haremlik divisions were rare in Ankara.

Unlike regions with milder climates, Ankara houses did not feature external wooden cladding. Aesthetic interest was provided through exposed brickwork within the wooden frame, often laid in zigzag patterns without plastering. While exteriors were simple, interiors were richly ornamented with intricate woodwork and painting, particularly on ceilings and hayat sections. Tile decorations were rare. Doors were equipped with iron or bronze knockers and rings. From the 17th century, more windows and oriels were added, creating livelier facades. Stone walls gave way to wooden frames, while western-style iron window grilles became popular in the modernization period. Lattice and sash windows spread in the 19th century. Following earthquakes and fires in the late 19th century, masonry houses began to appear.

An Ankara house with a seyregâh, located in Sakarya Neighborhood, near Hamamönü in Ankara. What sets this seyregâh, with its roof covered and eaves wide enough to be supported by wooden columns, apart from other examples is that its ceiling features late-period hand-painted decorations instead of traditional wooden lathwork.

Modern Developments and Destruction

Ankara’s Municipality Council was founded in 1872, and architectural changes began during the westernization period, though the timber-frame infill style remained prevalent.

In the late 18th century, declining central authority and the rise of banditry and corruption among city leaders disrupted trade, though the city’s physical appearance changed little. In the 19th century, vineyard houses (bağ evleri) began to surround Ankara in areas such as Keçiören, Ayvalı, Etlik, Tuzluçayır, Mamak, Kayaş, Gaziosmanpaşa, Çankaya, Dikmen, Ayrancı, and Esat.

Sakarya Neighborhood, also known as Boşnak Mahallesi, established in 1878, was Ankara’s first planned district with straight, grid-like roads. Houses were pre-built for immigrants from the Balkans, eroding traditional Ankara house characteristics. The first street grids also appeared here.

After Ankara became the capital following the Republic’s proclamation, two visions emerged: either develop the old city while preserving its heritage or build a new city alongside. However, factors such as lack of maintenance, functional conversions (especially into commercial spaces), and structural alterations led to the continuous destruction of the historical fabric.

In 1926-1928, German archaeologists Kreneker and Schede excavated around the Temple of Augustus, leading to the demolition of nearby houses. In 1937, remaining houses were cleared to create open space around Hacı Bayram Mosque. Further destruction followed with the opening of Ulucanlar Avenue in 1955 and the construction of Hacettepe Hospital in the 1960s, along with new boulevards, all contributing to the loss of historical neighborhoods.

Surrounded by informal settlements (i.e. slum “gecekondu”), old Ankara is now hemmed in by multi-story buildings along main avenues. Economic decline led residents of Kaleiçi and Kalealtı to move out, replaced by lower-income migrants unable to maintain the houses. Despite these challenges, the area still retains significant cultural value, with many houses still used as residences. Some have been converted into cafes, bars, restaurants, shops, and cultural centers, especially in the Dışkale area.

For those interested in traditional Turkish architecture, the Open-Air Museum called “Living Village” (Yaşayan Köy) in Beypazarı, near Ankara, offers restored Turkish houses, similar to those in Odunpazarı (Eskişehir), Safranbolu (Bartın), and Ankara’s own Beypazarı. Visitors can stay in these traditional houses and sample authentic local cuisine.

You can refer to the book “Imagining the Turkish House” by Carel Bertram for more information.