When people think of the Ottoman Empire, images of grand palaces, sultans, and the harem often come to mind. Yet, one of the most mysterious and misunderstood figures within this world is the Ottoman harem aghas; a eunuch who wielded significant power behind palace walls. The lives of these individuals, especially during the height of the Ottoman Empire, are full of fascinating details that defy common assumptions.

Black Eunuchs vs. White Eunuchs

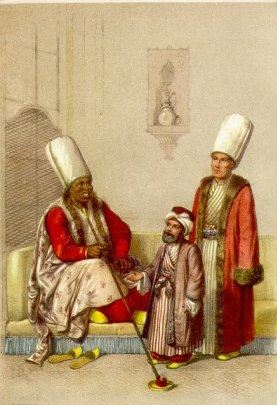

The harem aghas were typically divided into two main groups: black eunuchs and white eunuchs. Black eunuchs, often from East Africa, were castrated before puberty and brought to the Ottoman Empire through the slave trade. They were considered more loyal and less threatening to the royal women, which is why they were assigned to the harem. White eunuchs, usually from the Balkans or Caucasus, had administrative and educational duties in other parts of the palace.

Over time, black eunuchs gained more power, especially the Chief Black Eunuch (Kızlar Ağası), who became one of the most influential figures in the palace, acting as an intermediary between the sultan and the harem.

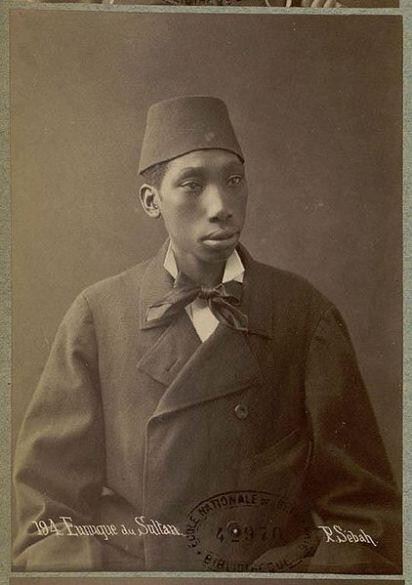

A photograph of a “harem agha” taken in 1870.

Not Just Servants – Power Brokers of the Palace

Contrary to the assumption that harem aghas were merely servants, they often held strategic political influence. The Chief Black Eunuch had direct access to the Valide Sultan (the sultan’s mother) and sometimes even the sultan himself. This access allowed them to influence decisions, recommend appointments, and even play roles in royal successions.

Their political importance grew so much that some aghas were able to accumulate wealth, own properties, and sponsor architectural works in Istanbul and beyond.

Castration of Ottoman Harem Aghas: A Harsh Reality

The process of becoming a eunuch was brutally painful and risky. Most black eunuchs were forcibly castrated at a young age, often around 7 or 8 years old, after being kidnapped from Africa by Arab slave traders. The process was carried out under primitive and brutal conditions, and only about one in ten survived the operation. Those who lived were later trained and brought into palace service.

As described in Gökhan Akçura’s book Ay’a Seyahat, the reality of their lives extended beyond physical suffering. Contrary to common assumptions, harem aghas retained deep emotional and even sexual attachments to women. Akçura writes:

“Despite having had their genitals removed, harem aghas loved women. Their feelings in this regard were intense. In palaces, a harem agha would choose a beautiful young woman to love. That woman would become his favorite, his own possession. He would protect and watch over her. The harem agha was jealous and could become cruel or even violent. If his beloved caught the attention of his master, the agha would become desperate, enraged, even mad. Threats, tears, emotional breakdowns; these were all signs of a love that could not be satisfied or soothed.

Despite lacking reproductive organs, harem aghas retained a full and even exaggerated sense of sexuality. This instinct was not primitive but highly developed. The harem agha loved and found pleasure in intimacy. He would try to satisfy his beloved by touching or using other methods. In fact, some harem aghas even got married.”

This complex and often tragic dimension of harem aghas challenges the simplistic view of them as neutral servants, revealing a more nuanced and deeply human narrative within the palace walls.

Education and Loyalty

Despite their traumatic origins, harem aghas were given education and training. Many were literate in Arabic, Turkish, and sometimes Persian. They were taught Islamic law, administration, and etiquette. Their loyalty was rewarded with high status, and they were often seen as guardians of moral and religious order within the palace.

Decline of Ottoman Harem Aghas with the Empire

As the Ottoman Empire began to decline in the 19th century, so too did the influence of the harem aghas. Reforms under Sultan Mahmud II and the Tanzimat Era reduced their powers, and the role of eunuchs in palace affairs diminished significantly. The harem came to an end after the abolition of the sultanate on November 1, 1922.

The story of the Ottoman harem aghas is more than just a tale of palace intrigue. It is a complex chapter in Ottoman history, blending themes of power, sacrifice, identity, and politics. These men, often born into suffering, rose to wield immense influence at the very heart of the empire. By understanding their role, we gain a deeper insight into the inner workings of one of history’s greatest empires.

The Last of Ottoman Harem Aghas: Sadi Yaylımateş

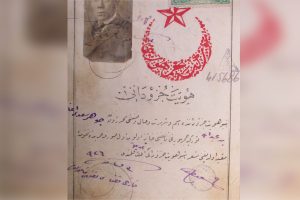

According to an identity document issued on April 3, 1926, by the Kartal Population Office for renewal purposes, Cevher Sadi Agha was born in Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia) in 1895. His father’s name was Abdullah, his mother’s name Havva, and his occupation was listed as a farmer.

At the age of eight, he was kidnapped by slave traders and taken to Alexandria, where he was castrated. After the operation, he was buried up to his waist in hot sand to recover. Once he was able to stand, he endured a very difficult sea journey to Istanbul; many died on the ship along the way.

After rigorous training, Sadi Agha began his duties at the Cihannüma Pavilion of Yıldız Palace, where his role was to attend to the princes.

He witnessed the reigns of three sultans; Abdülhamid II, Mehmed V Reşad, and Mehmed VI Vahdettin; as well as the last caliph, Abdülmecid II. Outside the palace, he lived in a house in Beşiktaş Akaretler that had been assigned to him, commuting to Yıldız Palace by bicycle.

Sadi Ağa (Yaylımateş)

Towering Figure with a Refined Ottoman Turkish

After leaving the palace, Sadi Agha was granted vast lands in Tuzla, on the side of the Infantry School facing the D-100 highway. He later sold these lands and purchased a house and plot in the İstasyon (Station) neighborhood.

In this neighborhood, he lived in a two-story stone house with a woman whom children called haminne (granny). Known as Sadi Yaylımateş, he was polite and spoke beautifully in refined palace-era Ottoman Turkish.

Like many harem aghas who lived long before him; Abbas Agha, Mehmed Agha, Cafer Agha, and Beşir Agha; Sadi Agha also commissioned the construction of a mosque.

One of the properties he donated is now the site of the İstasyon Dörtyol Mosque (also known as İstasyon Çinili Mosque), built in 1970.

The land of the old İstasyon Health Clinic, next to the mosque, was also donated by him.

Although the mosque does not bear his name, two streets in the neighborhood are named after him: Sadi Bey Street and Yaylım Street.

Standing nearly two meters tall with dark skin, Sadi Agha had an imposing appearance. He also kept bees and sold honey from nearly 50 beehives, with all proceeds donated to charity. During the day, he would eat at Süslü Ahmet’s restaurant, sit at Kambur Hakkı’s café, and chat with neighbors and friends. Some nights, he would join his neighbors and walk to the Tuzla coast to watch films at Hamdi Usta’s cinema.

Other harem aghas such as Nadir Agha from Göztepe and Cafer Agha, who had initially come with him to Tuzla but later left, used to visit him.

The identity document issued to Sadi Yaylımateş by the Kartal Population Office on April 3, 1926.

The End of an Era and the Art of Silence

Sadi Yaylımateş, one of the last harem aghas to leave a mark on Tuzla’s recent history, passed away on Thursday, February 27, 1975, at his home in Postane Neighborhood, Tuzla. He was buried in the Tuzla Cemetery.

He never spoke to journalists. During his lifetime, Sadi Bey consistently rejected interview requests from journalists. In his 1998 novel Meyyâle, journalist Hıfzı Topuz described him as:

“He wouldn’t open his mouth to say a single word.”

Even before the novel, Topuz had tried to feature Yaylımateş:

“Today, I found one of the last harem aghas, Sadi Agha (Sadi Yaylımateş), in a café in Tuzla. He didn’t want to say a single word about his past. ‘We’ve long forgotten the past. Let’s focus on the present. We are uneducated people. What would we know anyway…’ he said. Melih Cevdet also tried hard to make Sadi Agha talk. Despite all efforts, we couldn’t get a single word out of him.”