The Importance of Water in Istanbul’s Urban History

Water is one of the primary indicators of whether a place has evolved into a proper city. Throughout history, settlements have typically formed near water sources. Though Istanbul lacks significant rivers, its unique geography necessitated innovative solutions to water supply. For centuries, water was brought to the city via aqueducts from as far as the Istranca Mountains, hundreds of kilometers away.

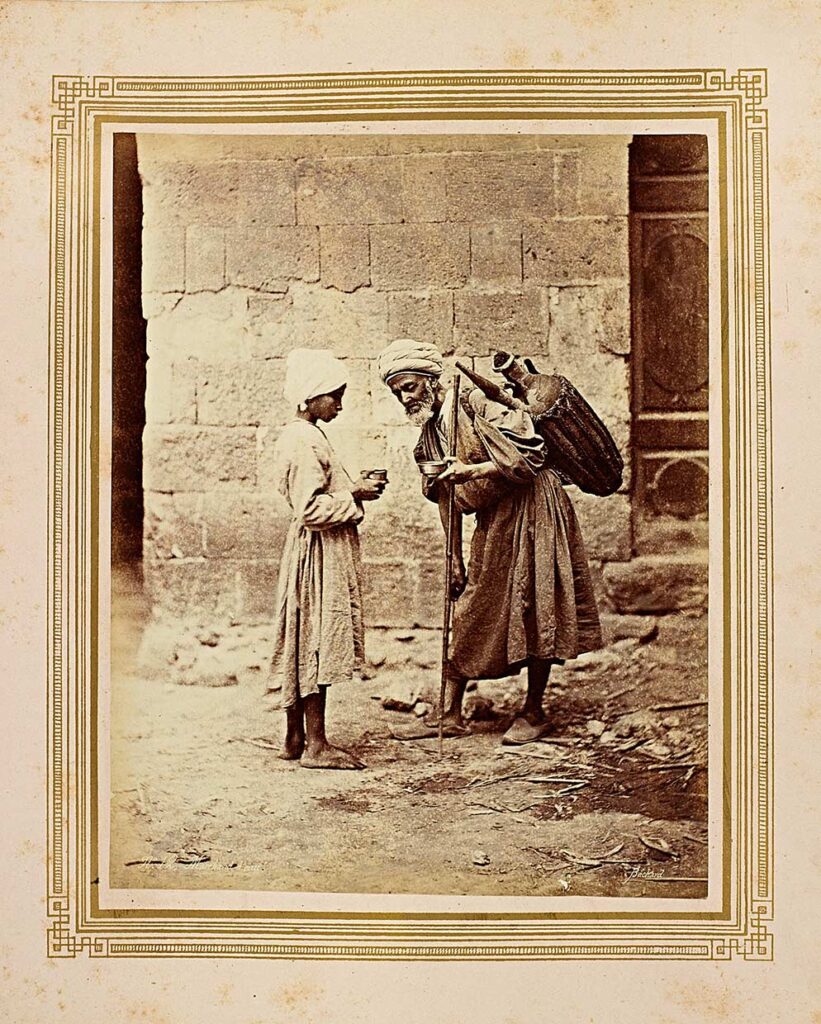

In addition to the piped water, Istanbul also became renowned for the quality of its spring, underground, and natural source waters. These waters; described in old texts as ab-ı hayat (water of life), mai-leziz (delicious water), ab-ı leziz, or miyah-ı nefise (fine waters); became a source of delight for the city’s inhabitants. “In old Istanbul, there were water enthusiasts and connoisseurs who could tell whether the water they were drinking came from Taşdelen, Karakulak, or Sırmakeş and would seek out their preferred source,” we are told. To facilitate access to these pristine waters, a formal “Saka Organization” was established. These sakas, or water carriers, filled leather skins holding 45–50 liters and delivered water directly to homes.

From Roman Aqueducts to Ottoman Engineering

Before the Ottoman conquest, the Roman city of Byzantium used aqueducts to bring water.After the conquest, Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror made additions to this system and maintained it. When building his first palace, he even chose Bayezid Hill specifically because of its water access. According to the famous Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi:

“Sultan Mehmed, a man of nature, once gathered all his physicians and asked them, ‘Which is the finest water in Istanbul?’ They replied that the Şem’un Spring in the Old Palace had the lightest and most pleasant taste. The waters of other springs were absorbed in equal amounts by cotton pads and then sun-dried. The cotton soaked in Şem’un’s water turned out to be the lightest. From then on, the sultan drank only this water.”

A water’s drinkability was often judged by how light it felt in the stomach and whether it caused bloating or discomfort.

Legendary Water Springs of Istanbul

It is said that the Asian (Anatolian) side of Istanbul has more natural springs than the European (Rumeli) side. On the European side, famous springs include Kestane, Çırçır, Ayazma Hünkâr, Fındık, Fıstık, and Hamidiye.

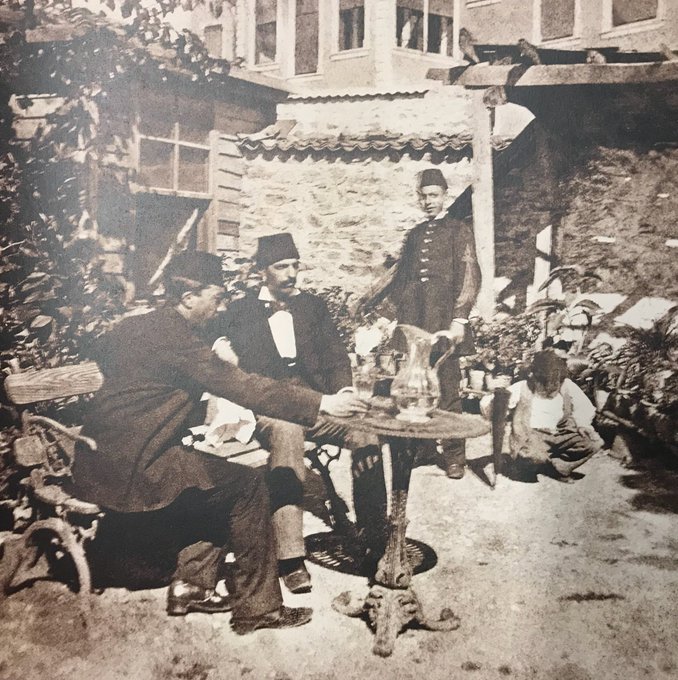

On the Asian side, the most famous are: Çamlıca, Kayışdağı, Taşdelen, Karakulak and Sırmakeş.These waters were sometimes sent to the Holy Lands during pilgrimage and brought back reverently. Even Young Turks (Jöntürks) and diplomats traveling to Europe took these famous waters with them. Likewise, those awaiting visitors from Istanbul would request these waters, longing for even a single sip.

All water-related records were kept in the office of the kadi (judge) of Eyüp, one of Istanbul’s four legal districts. Islamic law permits the buying and selling of water extracted from underground through human effort. These spring waters, treated almost like private property, have been distributed by individuals from past to present.

Iconic Water Sources of Istanbul and Their Legacy

The Çamlıca waters on the Asian side were distributed across the region by figures like Nurbanu Sultan, Nevşehirli Damad İbrahim Pasha, and Sultan Selim III.İbrahim Pasha, who built many water structures in Üsküdar, left behind a “Map of Üsküdar’s Water Routes,” still preserved at the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts.

Kayışdağı, one of Istanbul’s highest hills, is rich in springs, generally known as Kayışdağı Waters. In use since the 17th century, these waters flowed from fountains across the city and remained a favorite for many years.

In Beykoz’s Akbaba and Dereseki villages, multiple spring sources exist, with Karakulak and Sırmakeş being the most famous.

The Karakulak spring was created in the 18th century by Ahmed Ağa by collecting small individual sources. It is considered one of the finest waters of the Empire. In the 18th and 19th centuries, this water was transported to the palace in sealed silver jugs. The last Caliph, Abdülmecid Efendi, was reportedly a devoted admirer. Ahmed Ağa’s tomb; distinctive for being the only protruding grave in the Dereseki Cemetery; is located on the path to the Karakulak spring and seems to silently request a prayer from passersby.

The Sırmakeş spring originated on the estate of Ahmed Midhat Efendi, famously known as the “Writing Machine.” He used to bring the water from Beykoz to his office in the historic city center daily and sold it. During the late Ottoman period Sırmakeş water was often among the diplomatic gifts sent abroad. These bottles, decorated in traditional Ottoman style, were presented to foreign ambassadors.

Taşdelen water, sourced from Alemdağ, has an even older history. It was endowed by Nurbanu Sultan, wife of Sultan Selim II. Like Karakulak, Taşdelen water was carried by pilgrims heading for Hajj. On the return trip, the water containers were filled with Zamzam, earning Taşdelen the reverent title of “Zamzam’s Companion.”[5]

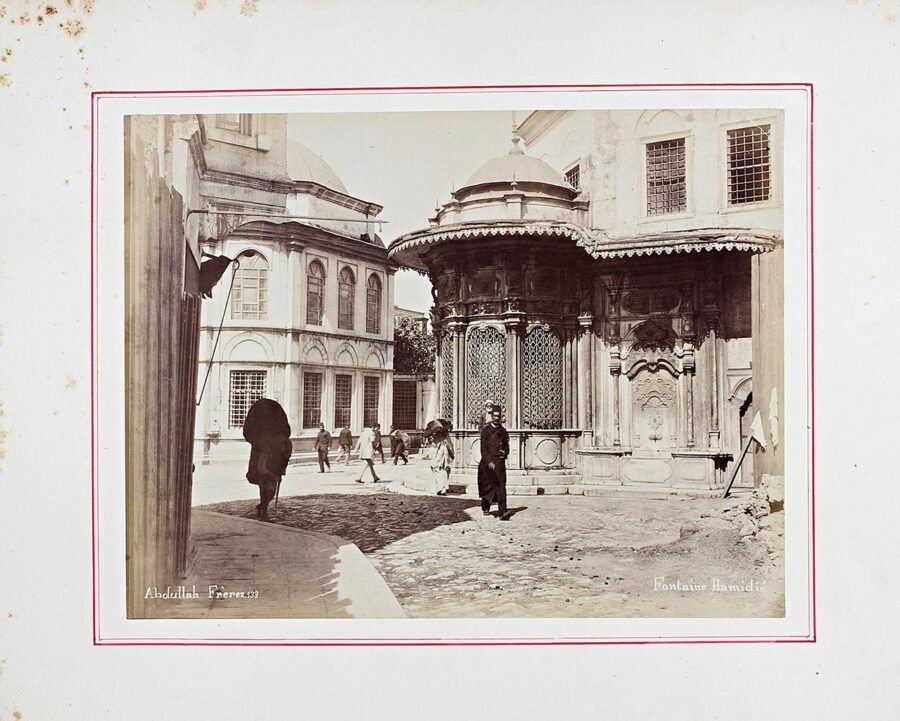

Among the newer European-side waters is Hamidiye, created by combining more than sixty springs in Kemerburgaz. Still available today, its famous slogan is: “Everyone falls silent at the name of Hamidiye.” Provided by Sultan Abdülhamid II through 133 fountains, it was the first in the empire to use cast iron pipes instead of baked clay.

Çırçır and Kestane springs in Sarıyer, known for their slow trickle, were even prescribed to patients suffering from kidney stones. The Hünkâr, Fındık, and Fıstık springs; also in Sarıyer; spring from nearby locations. Some of these areas, formerly picnic spots, retain their recreational charm today.

When Sultan Abdülhamid II was still a prince residing at Kağıthane Sadabad, he developed a fondness for the Ayazma Spring, which flowed just across from today’s Ottoman Archives building. Once he became sultan, he had it piped to his Yıldız Palace using the latest technology.

A Timeless Symbol of Taste and Culture

Istanbul’s spring waters are so numerous and culturally rich that they could fill volumes. Water has long held a prestigious place in Istanbul’s social life, literature, and ceremonies. Being an Istanbulee is, in part, about having a refined palate; and at the top of that list is water. May you drink joyfully from the many life-giving springs of Istanbul, bringing vigor to your body and health to your spirit…