In the early 1930s, Europe was entering one of its darkest periods. With Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Nazi policies rapidly targeted Jews, intellectuals, and political dissidents. Among those most at risk were leading scientists, suddenly dismissed from their positions and threatened with imprisonment. It was in this climate of fear that Professor Philipp Schwartz fled to Switzerland and established the Notgemeinschaft deutscher Wissenschaftler im Ausland (Association of German Scientists Abroad). His mission was urgent: to find safe havens for persecuted Nazi-era scientists and secure their futures. Yet, many European countries hesitated to open their doors to these refugees, leaving their fate uncertain.

Turkey’s Bold Decision and University Reform

At the same time, Minister of National Education Reşit Galip contacted Schwartz as part of the 1933 University Reform. After negotiations, an agreement was signed on July 6, 1933. According to the agreement, scientists would work full-time, prepare to teach in Turkish within three years, and submit reports to the government if necessary. Despite its limited economic resources, Turkey offered higher salaries than typical professor wages. This initiative saved more than 150 academics from Nazi persecution.

Scientific Advancement in Turkey

These scientists not only taught but transformed Turkey’s academic structure:

- Hans Reichenbach – Introduced the teaching of mathematical logic.

- Walther Kranz – Established courses in philology, Latin, and Ancient Greek.

- Albert Eckstein – Advanced child healthcare and helped eliminate the noma epidemic.

- Clemens Holzmeister – Oversaw key architectural projects, including the Turkish Grand National Assembly building.

- Carl Ebert & Paul Hindemith – Laid the foundations for the conservatory and symphony orchestra.

- Fritz Arndt – Translated scientific terms into Turkish (“solution,” “dilute,” etc.).

- Rudolf Nissen – Performed free surgeries across the country.

Among them were world-class figures such as nanotechnology pioneer Von Hippel and Finlay Freundlich, assistant to Einstein, who revitalized Turkey’s astronomy education.

The Kantorowicz Case: Atatürk’s Personal Intervention

Dentist Alfred Kantorowicz was imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp. His name was initially marked as “unsalvageable” on Schwartz’s list. However, Atatürk stated, “I want him personally.” Turkey formally requested his release. The first request was ignored, but a second, firmer appeal led to Kantorowicz’s freedom.

Loyalty and Resistance During the War

Many of these scientists showed deep commitment to Turkey:

- Hugo Braun: “Even the ocean’s depths refused us, yet Turkey embraced us.”

- Von Hippel: “Here we became fully Turkish. We found a new homeland.”

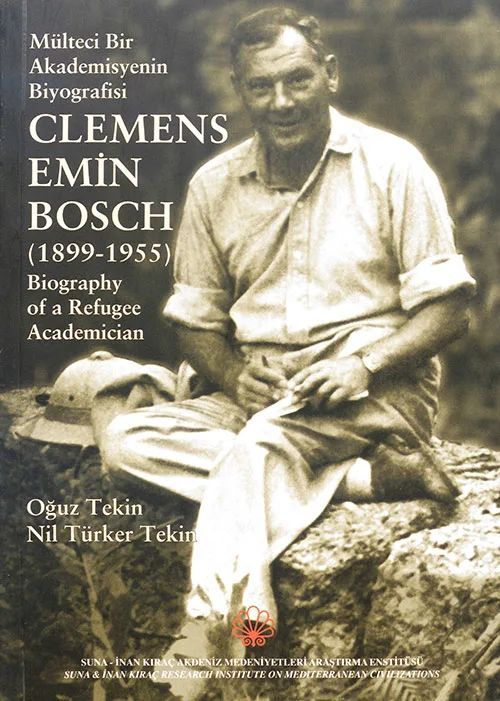

- Clemens Bosch (Emin): Converted to Islam and became a Turkish citizen.

During the war, the Nazis attempted to reclaim these scientists by offering top German scholars and salaries, but Turkey refused.

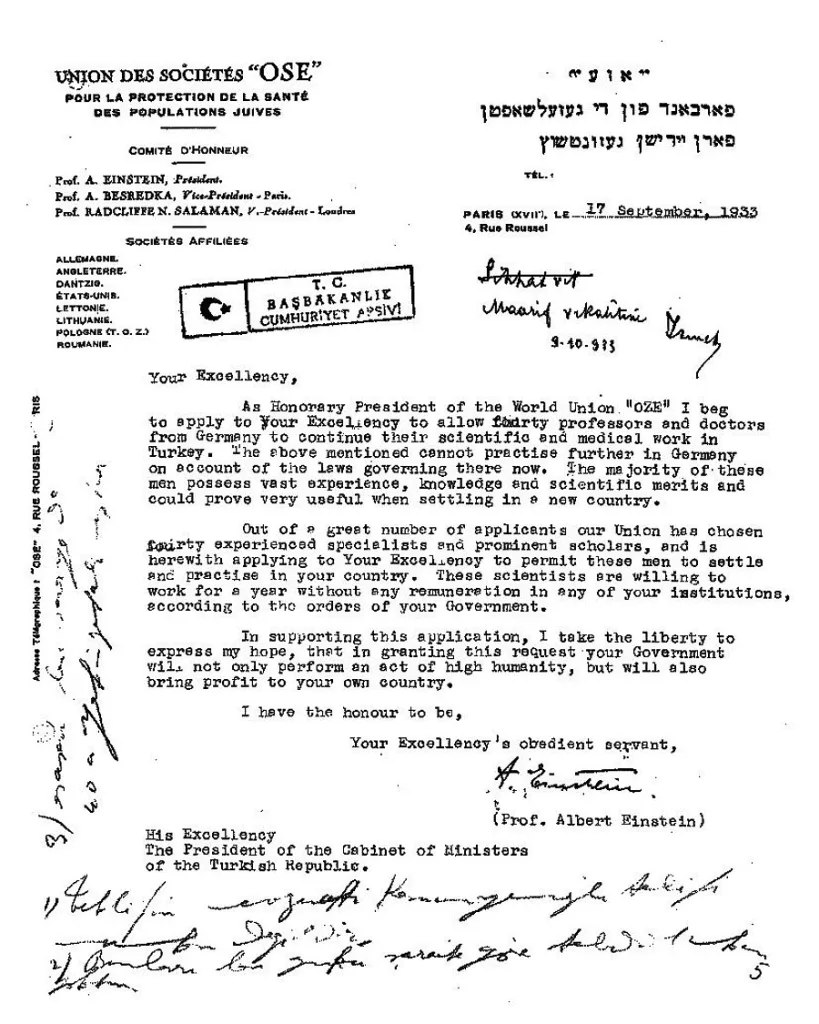

Einstein’s Letter and Turkey’s Capacity

Before seeking refuge in the U.S., Einstein attempted to help the remaining scientists. In a letter to Turkey, he proposed the acceptance of 40 individuals (Israel State Archives, Doc. 54). However, due to the limited number of universities and budget constraints, Turkey regretfully declined.

Legacy and Impact

Between 1933 and 1945, these academics initiated a “golden age” in Turkish education and science. Although post-WWII American influence slowed this momentum, Turkey’s humanitarian and visionary decision left a lasting mark on history.

Further References

The interested audience can refer to following sources for more information:

- Schwartz, Philipp. Notgemeinschaft: Rettung jüdischer Wissenschaftler 1933–1939. Zürich, 1953.

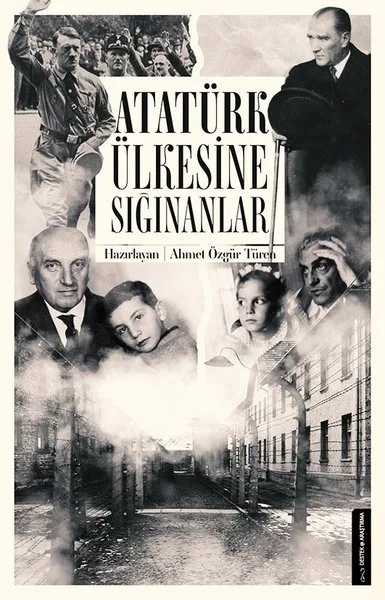

- Türen, Ahmet Özgür. Atatürk’ün Ülkesine Sığınanlar. Istanbul, 2015.

- Reisman, Arnold. Turkey’s Modernization: Refugees from Nazism and Atatürk’s Vision. New Academia Publishing, 2006.

- Freundlich, E. “Astronomy in Turkey.” Nature, 1948.