In a cuneiform tablet describing the Assyrian campaign of 856 BCE, it is recorded that the Assyrian army halted at Tushpa –the city that would later become the capital of Urartu- and there received tribute.

Assyrian sources of the period refer to Lake Van as the “Upper Sea”. On the eastern shore of this great inland lake -1,665 meters above sea level- the Kingdom of Urartu, one of the most significant states of the Anatolian Iron Age, emerged in the mid-9th century BCE. At its heart was Tushpa, today known as the Van Fortress, founded by King Sarduri I, the son of Lutibri. In six nearly identical foundation inscriptions carved into stone, Sarduri proclaimed the birth of his capital and his rule:

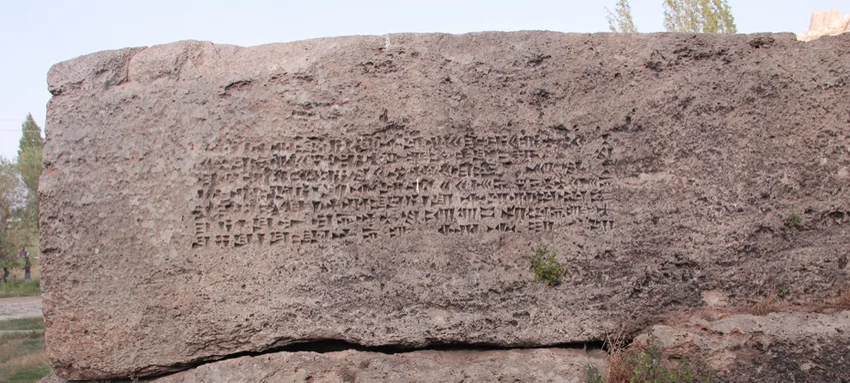

Inscription of Sarduri, son of Lutibri, great king, mighty king, king of the world, king of Nairi, unmatched king, admirable shepherd, fearless in battle, subduer of rebels: I, Sarduri, son of Lutibri, king of kings, receiver of tribute from all rulers, brought these stone blocks from the city of Alniunu and built this wall.

The name “Urartu” is the term used by the great kings of Assyria for their formidable rivals to the north. The Urartians themselves called their realm Biaini and referred to themselves as the people of Nairi.

The Sardur Bastion inscription proclaiming the foundation of the capital and the kingdom.

From Kingdom to Empire

From the reign of Sarduri I onward, permanent settlements began to appear around Tushpa. Over the next two centuries, Urartu extended its power from the Caucasus and the Kura River Basin to the Southeastern Taurus Mountains, and from Malatya and the Euphrates Basin to northwestern Iran and Lake Urmia.

The Urartian kings established numerous royal cities and settlements across their vast domain, introducing a new socio-economic model to regions that had never known centralized authority. Urban centers, some housing tens of thousands, were supported by large-scale irrigation systems, canals, vineyards, orchards, and fortifications. Agriculture and animal husbandry formed the economic base, but the construction of monumental works required a massive labor force.

Assyrian and Urartian inscriptions reveal the forced relocation of populations; sometimes numbering hundreds of thousands. One Urartian text boasts:

“…In the same year, I marched against the land of Urme, captured its 11 fortresses, and destroyed them. From there I deported men and women: 1,100 men, 6,500 women, 2,000 fighting men, 2,538 cattle, and 8,000 sheep…”

By the late 9th century BCE, Urartu had grown into what can rightly be called an empire; although archaeological evidence suggests that many of its cities were founded during this very period, with few earlier layers beneath. Pottery with distinctive grooves from the Early Iron Age, found across eastern Anatolia, the Caucasus, and northwestern Iran, links Urartu to earlier cultures, yet provides no direct proof of its political origins.

Urartu Kingdom borders

Uruatri and Nairi: Peoples Who Resisted Assyria

Written sources are scarce for Urartu’s formative period. Some Soviet-era theories -still influential in scholarship- hold that groups referred to in Assyrian records as Uruatri and Nairi (attested since the reign of Shalmaneser I in the 13th century BCE) were local highland peoples who resisted Assyrian expansion, later coalescing into the Urartian state.

Linguistically, Urartian is distantly related to Hurrian, spoken in the 2nd millennium BCE in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and surrounding regions. Urartu also adopted certain Hurrian deities. However, Hurrian cultural influence was so widespread that it cannot alone explain the emergence of Urartu as a centralized state.

Before the appearance of the first Urartian inscriptions in the late 9th century BCE, the only written evidence comes from Assyrian royal annals, documents steeped in propaganda. Assyrian scribes often exaggerated the status of local chieftains, calling them “kings” to magnify their own victories.

The annals located at the entrance of the Argišti Rock Tomb (Van Fortress).

Urartu as a Political Term

By the reigns of Ashurnasirpal II and Shalmaneser III (early 9th century BCE), the name Urartu in Assyrian texts had shifted from a vague geographic label to a clear political designation. This change coincided with the rise of formidable rivals such as Aramu and Sarduri.

Aramu, mentioned in Shalmaneser III’s annals around 859 BCE, ruled from the fortified city of Sugunia. Whether he belonged to the same dynasty as Sarduri remains uncertain, Sarduri’s own inscriptions name his father as Lutibri, not Aramu. The political picture suggests multiple local rulers before the consolidation of the kingdom.

Nairi and Assyrian Control

The term Nairi appears in Assyrian records for over five centuries, often in formulas such as: “I fought against the kings of the lands of Nairi and received tribute from them.” Tiglath-pileser I claimed to have pursued 60 Nairian kings to the shores of the “Upper Sea” (Lake Van). This label likely referred to a cluster of highland principalities, rather than a single polity.

In the 9th century BCE, Ashurnasirpal II campaigned deep into the Upper Tigris region -Nairi’s southern border- installing governors, levying tribute, and even taking the sons of local rulers to be raised in the Assyrian court. These young hostages may have absorbed Assyrian military and administrative practices, later transferring them to Urartu. The similarity between early Urartian royal titles and Assyrian formulas supports this idea.

Lake Van and Mt Suphan

Assyria’s Role in Urartu’s Rise

By 856 BCE, Assyrian armies were operating directly in the Tushpa region. The earliest mention of Tushpa in Assyrian records coincides with the period when Urartu was consolidating into a kingdom. While the precise dynamics remain unclear, Assyrian influence -both direct and indirect- was undoubtedly a catalyst.

Urartian culture bears unmistakable traces of Assyrian inspiration: the adoption of cuneiform script, royal titulature, monumental architecture, and centralized bureaucracy. These were the hallmarks of the ancient Mesopotamian state tradition, transplanted into the rugged highlands.

The Mountain Kingdom

The establishment of Urartu marked the beginning of a 200-year cultural and political era in eastern Anatolia. For the first time, the highlands saw cities with citadels, lower towns, necropolises, temples, palaces, and storehouses built to a standardized plan. Advanced metallurgy, large-scale irrigation, and complex statecraft- hallmarks of southern Mesopotamia-were now embedded in a northern mountain kingdom.

This transformation was not simply the evolution of local traditions but likely the result of a dynastic and cultural transfer -possibly involving a Nairian elite trained in Assyria- bringing the tools of empire to a new and formidable power: Urartu.