Let’s not say impossible; because they exist. The Kipchaks, who spoke Turkic, were like this. Russians called them Polovets, Byzantines Kumans, Hungarians Kun, and the Mongols and Chinese called them Kipchak. The blond Turks themselves used the names Kıpçak or Kıbçak. In Islamic history, they’re also known as Kipchaks. Russian historian Gumilev traces their blondness to Europoid ancestors, suggesting that Kipchaks descended from Europoid Dinlins, who lived in the Minusinsk Basin and the Altai during the Bronze Age.

Additionally, terms like palladi in the 11th-century Latin work of the Man from Bremen, valwen in 13th-century Middle High German and Latin texts, and xarteşk’n mentioned in the 12th-century Armenian book of Matthew of Edessa are direct word translations based on contact with these peoples. In both Turkic and other languages, Kipchak or Kuman are associated with the meaning “blond.” Among the Kipchaks, as in certain other Turkic tribes, blond hair and light-colored eyes were common. Some argue that Polovets, the Russian version of their ethnonym, sometimes referred not only to yellow but also to blue (eyes) in Slavic languages.

Who Were the Ancestors of the Kipchaks?

It is argued that it’s incorrect to define “Turk” based purely on bloodlines. Not all peoples bearing the Turkish name or speaking Turkic dialects descend from the same origin. The Asian Huns (called Hiong-nu by the Chinese) included many different peoples. We emphasize the word “included.” Those who accept the Hiong-nu as the sole ancestors of Turks are mistaken -they were ancestors not only of Turks but also of other peoples. They were more like a nomadic federation, rather than a “state” in the modern sense. Back then, there were no “states” as we understand them today- just leaders managing large or small groups.

As for those who preceded the Hiong-nu, we lack definitive information. However, the Kipchak tribe offers meaningful clues. They weren’t Turkmen, nor did they resemble them physically, yet they spoke Turkic.

Kipchak tombstones

How is this possible? Gumilev attributes the Kipchaks’ blondness to their Europoid ancestors. He claims that Kipchaks descended from the Europoid Dinlins of the Minusinsk Basin and the Altai during the Bronze Age. He notes that after they began living with the Kimaks and earlier formed part of the Huns, their racial traits changed, incorporating some Hun features. Although the Huns (or Hiong-nu, as the Chinese called them) were of Mongoloid race, Gumilev adds that their facial features somewhat resembled Native Americans. In 350 AD, when the Huns in China were targeted for extermination, many Chinese with high noses and beards were also killed. Thus, Kipchaks mixed with Kimaks did not stand out among broad-faced Europoids.

Gumilev records that the Kipchaks differed physically from their southern neighbors, the Turkmens, and that Chinese sources described the Kipchaks as blond-haired and blue-eyed. He notes that Mamluk ruler Sonkor was blond and, of course, Kipchak. In Hungary, their Kuman descendants were called çango due to their bright, curly blond hair and blue eyes, although darker individuals existed among them. The Russian nickname Poloves comes from polova, meaning “chaff” or “crumbled straw” in reference to their hair color. A 14th-century Arab geographer states that Kipchaks were distinct from other Turks due to their unique religiosity, courage, agility, beautiful faces, neat features, and nobility. During the first Russo-Kipchak conflicts around 1055, their pale eyes and blond hair were particularly noted.

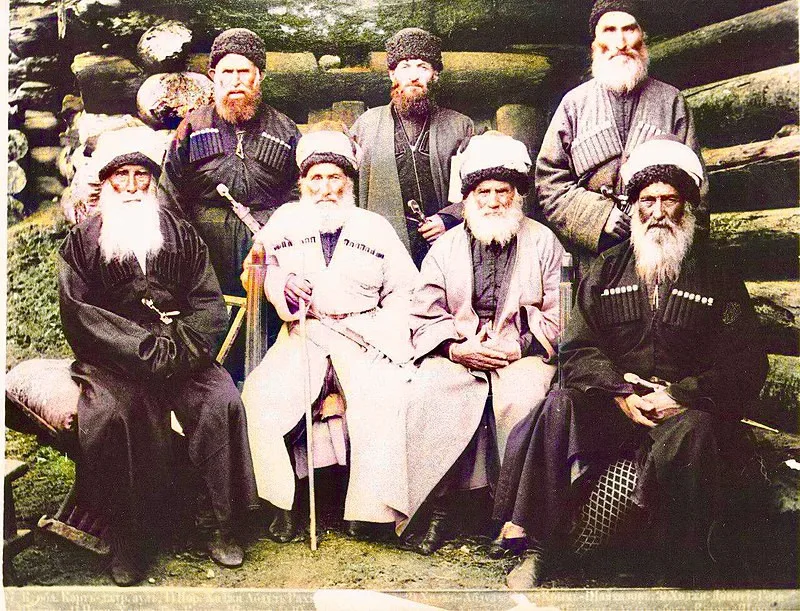

Karachay-Balkars

Among Kipchaks, Women Issued Orders Like Men

Russian historian A. Yakubovskiy mentions that Kipchaks did not obey the caliph’s laws and did not follow Islamic regulations. He cites Arab historian Al-Omari’s account regarding women’s status: “Al-Omari says: ‘The Kipchak people (unlike Iraqis and Persians) do not follow the caliph’s laws. Women participate equally in governance with men. Orders often come from them, even more so from women than from men… Truly, in our time or even in nearby times, we have neither seen nor heard of any woman with as much authority as them.’” Al-Omari lived between 1301 and 1384.

Kipchaks’ Descendants: Karachay and Balkar Peoples

Today, research shows that the Karachay and Balkar peoples of the Caucasus are descendants of the Kipchaks. They live in villages in high regions and deep valleys of the Caucasus Mountains. The Karachays live on one side of Mount Elbrus, the Balkars on the other. Apart from this geographical difference, there’s no distinction between them.

Their language belongs to the Western Turkic languages, classified in the Kipchak subgroup. It’s similar to Kumyk and Nogai languages spoken in the North Caucasus. Historical, anthropological, archaeological, and linguistic research shows that the Karachay-Balkar people are descended from Turkic tribes like the Huns, Kara-Bulgars, Alans, Khazars, and Kipchaks.

Kipchaks Built Human Statues Over Graves

In discussing 11th–13th century Kuman burial customs, A.Yu. Yakubovski cites G. Rubruquis: Kipchaks would create large mounds over graves and erect statues facing east, depicting a person holding a cup at stomach level. “The Kumans built pyramidal structures for the wealthy. I saw large towers made of brick in some places and stone houses in others, despite the absence of stone in that region. For the newly deceased, I saw 16 horse hides hung on poles arranged in four directions, and kumis for drinking and meat for eating placed in front of the grave. They said this was to honor the deceased’s ‘conversion’.” Here, conversion (tanassur) refers to Christianization, and the pyramid-shaped grave houses were called keşene.

Even After Conversion to Islam, Burial Traditions Persisted

The Karachay-Balkars encountered Islam relatively late, around the 18th century. But their adoption of Islam didn’t significantly alter their burial customs. They continued burying their dead according to older beliefs. Before Islam, they practiced a belief system centered on natural forces: a form of shamanism. Excavated Kipchak kurgans and graves in the Karachay-Balkar region illuminate these burial practices. Interestingly, pre-Islamic graves from the 14th to 18th centuries resemble Kipchak graves.

What Is Kara Kiygen?

Folklorist Ufuk Tavkul writes that mourning lasted long in Karachay-Balkar culture. Close relatives of the deceased wore only black clothing, called kara kiygen, to signal mourning. Mourning lasted forty days, but some wore black for a year or longer. In some cases, women mourned for life. Widows sometimes wore the clothes from the day their husband died for a full year without changing.

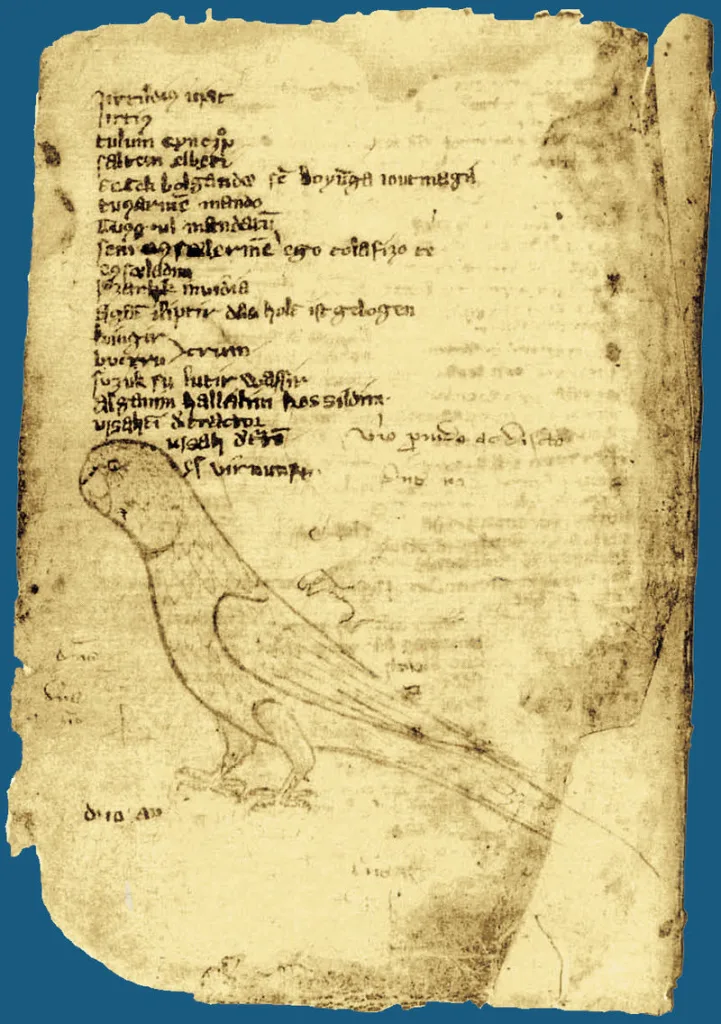

Codex Cumanicus

Europeans even compiled a famous book of Kipchak vocabulary: the Codex Cumanicus. Prepared in two parts by Germans and Italians, this work was created to help missionaries convert the Kipchak Kumans to Christianity. Though codex generally means “book,” here it’s more like “rules and dictations for the Kumans”:a rough but explanatory translation.

A bit about the Codex Cumanicus: The city of Saray, capital of the Golden Horde -a Kipchak city- became a major center of trade and culture, attracting Genoese and Venetian merchants. The Codex Cumanicus comprises two distinct notebooks. The first, compiled by Italian merchants to ease trade with Kipchaks and Persian-speaking Ilkhanids, is a grammar and dictionary. It includes Latin words with their Kipchak and Persian equivalents, covering not only trade goods but also religious terms, food, drink, animal names, and much more. This Italian Codex contains 55 pages.

Kipchak Balbal

The second notebook, the German Codex, was written by missionaries and includes Christian stories, Bible excerpts, hymns, sermons, 47 riddles, conjugations of the verb aŋla- (to understand), two pages of Latin-written Kipchak grammar, and lists of words and phrases. It’s a patchwork of unrelated pages written by various hands using different scripts.

The Codex Cumanicus is invaluable for understanding both the Kipchak group and Turkic dialects overall, as its alphabet more accurately reflects the spoken language than the Arabic script used elsewhere. The work was first mentioned by Tomasini in 1656 and was published scientifically by Comes Geza Kuun in 1880.